클로저(Closure): 자바스크립트의 가장 강력한 무기 (대규모 업데이트)

함수가 선언될 때의 렉시컬 환경(Lexical Environment)을 기억하는 현상. React Hooks의 원리이자 정보 은닉의 핵심 키.

함수가 선언될 때의 렉시컬 환경(Lexical Environment)을 기억하는 현상. React Hooks의 원리이자 정보 은닉의 핵심 키.

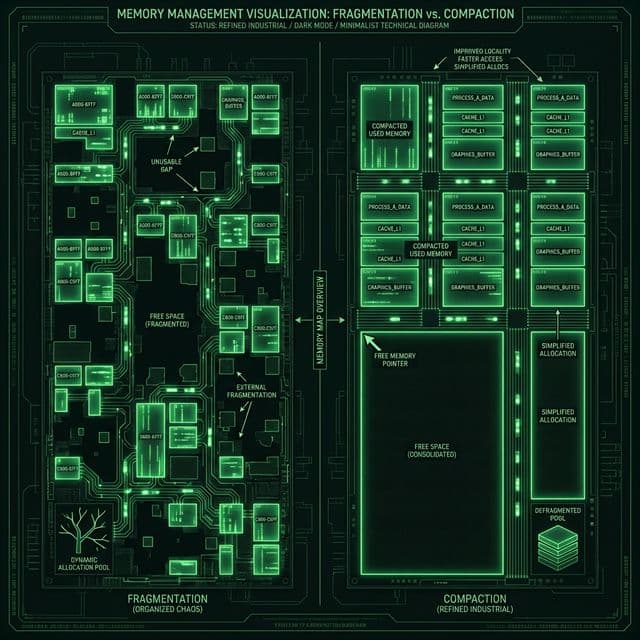

내 서버는 왜 걸핏하면 뻗을까? OS가 한정된 메모리를 쪼개 쓰는 처절한 사투. 단편화(Fragmentation)와의 전쟁.

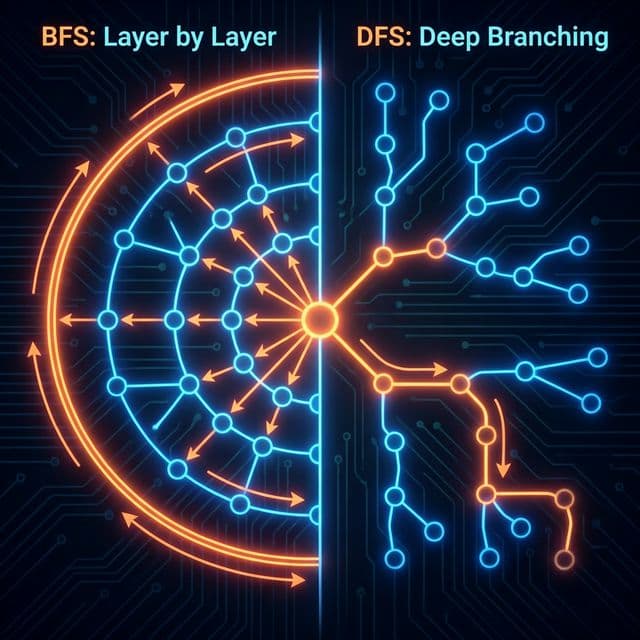

미로를 탈출하는 두 가지 방법. 넓게 퍼져나갈 것인가(BFS), 한 우물만 팔 것인가(DFS). 최단 경로는 누가 찾을까?

프론트엔드 개발자가 알아야 할 4가지 저장소의 차이점과 보안 이슈(XSS, CSRF), 그리고 언제 무엇을 써야 하는지에 대한 명확한 기준.

이름부터 빠릅니다. 피벗(Pivot)을 기준으로 나누고 또 나누는 분할 정복 알고리즘. 왜 최악엔 느린데도 가장 많이 쓰일까요?

클로저(Closure)를 처음 마주했을 때, 나는 도저히 이해할 수 없었다.

"함수가 이미 실행 완료되어 스택에서 사라졌는데, 어떻게 그 안의 지역 변수가 아직도 살아있지?"

C나 Java를 먼저 배운 사람일수록 더 혼란스러운 개념이다. 왜냐하면 전통적인 컴파일 언어에서는 함수가 종료되면 그 함수의 지역 변수는 스택 메모리에서 무조건 제거되기 때문이다. 이것이 정상적인 생명 주기다.

그런데 자바스크립트에서는 다르다. 함수가 죽어도 변수가 살아남는 기묘한 현상이 일어난다. 마치 좀비처럼.

function createWallet() {

let balance = 100; // 지역 변수 (함수 끝나면 사라져야 정상)

return {

deposit: function(amount) {

balance += amount; // 근데 여기서 balance를 계속 쓰네?

return balance;

},

withdraw: function(amount) {

balance -= amount;

return balance;

}

};

}

const myWallet = createWallet(); // createWallet 실행 완료. balance는 죽었어야 한다.

console.log(myWallet.deposit(50)); // 150 (balance가 살아있다!)

console.log(myWallet.withdraw(30)); // 120 (계속 살아있다!)

console.log(myWallet.balance); // undefined (직접 접근은 불가)

createWallet 함수는 실행이 끝나고 콜 스택에서 사라졌다. 그런데 balance 변수는 어떻게 살아남았을까? 게다가 외부에서 myWallet.balance로 직접 접근할 수 없으니 완벽한 정보 은닉(Encapsulation)까지 달성했다.

이것이 바로 클로저(Closure)다.

나는 이걸 이렇게 받아들였다: "함수가 태어난 곳의 환경을 평생 기억하는 주민등록증을 가지고 다니는 것"이라고.

클로저를 제대로 이해하려면 먼저 렉시컬 스코프(Lexical Scoping)를 완전히 정복해야 한다. 나는 이 개념을 이해하는 데 꽤 시간이 걸렸다.

자바스크립트는 함수를 어디서 호출했느냐가 아니라, 어디에 선언했느냐로 상위 스코프를 결정한다.

const globalVar = "나는 전역";

function outerFunc() {

const outerVar = "나는 outer";

function innerFunc() {

const innerVar = "나는 inner";

console.log(innerVar); // 내 변수

console.log(outerVar); // 부모 변수 (여기가 핵심!)

console.log(globalVar); // 조부모 변수

}

innerFunc();

}

outerFunc();

// "나는 inner"

// "나는 outer"

// "나는 전역"

여기서 중요한 점은 innerFunc가 outerVar에 접근할 수 있다는 것이다. 왜? innerFunc가 outerFunc 안에서 선언(태어났기)되었기 때문이다.

함수가 생성되는 순간, 자바스크립트 엔진은 함수 객체 내부에 [[Environment]]라는 숨겨진 프로퍼티를 만든다. 이 프로퍼티는 함수가 태어난 렉시컬 환경(부모 스코프)을 가리킨다.

마치 사람이 태어날 때 부모의 DNA를 물려받듯이, 함수도 태어날 때 부모 스코프의 참조를 물려받는 것이다.

graph TD

A[Global Execution Context] --> B[outerFunc Execution Context]

B --> C[innerFunc Execution Context]

subgraph Global Scope

globalVar

end

subgraph Outer Scope

outerVar

end

subgraph Inner Scope

innerVar

end

C -.->|찾을때 거슬러 올라감| B

B -.->|찾을때 거슬러 올라감| A

함수가 실행될 때 변수를 찾는 과정:

[[Environment]]가 가리키는 부모 스코프로 올라간다.ReferenceError.이걸 스코프 체인(Scope Chain)이라고 한다. 나는 이걸 "족보를 거슬러 올라가는 것"이라고 정리해본다.

클로저의 본질을 깨달은 건 React Hooks를 공부하던 중이었다.

function makeCounter() {

let count = 0; // 이 변수가 핵심

return function() {

return ++count;

};

}

const counter1 = makeCounter();

const counter2 = makeCounter();

console.log(counter1()); // 1

console.log(counter1()); // 2

console.log(counter2()); // 1 (독립적!)

console.log(counter1()); // 3

각 counter는 자신만의 독립적인 count 변수를 가진다. makeCounter를 호출할 때마다 새로운 렉시컬 환경이 만들어지고, 반환된 함수는 그 환경을 클로저로 캡처한다.

이제 와닿았다. 클로저는 단순히 "변수를 기억하는 것"이 아니라, "함수가 태어난 그 순간의 환경 전체를 스냅샷처럼 보존하는 것"이었다.

클로저를 이해하는 데 가장 도움이 된 비유는 타임캡슐이다.

타임캡슐을 묻은 시점(함수 선언 시점)의 환경을 나중에(함수 실행 시점) 다시 꺼내 쓸 수 있는 것. 이것이 클로저다.

자바스크립트에는 오랫동안 private 키워드가 없었다. ES2022에서야 #privateField 문법이 추가됐지만, 그 전까지는 클로저가 유일한 방법이었다.

function createPerson(name, age) {

// Private variables (외부에서 접근 불가)

let _name = name;

let _age = age;

let _ssn = "123-45-6789"; // 민감 정보

// Public methods (외부에 노출)

return {

getName: function() {

return _name;

},

getAge: function() {

return _age;

},

setAge: function(newAge) {

if (newAge > 0 && newAge < 150) { // 유효성 검증

_age = newAge;

}

},

introduce: function() {

return `안녕, 나는 ${_name}이고 ${_age}살이야.`;

}

// _ssn에 접근하는 메서드는 의도적으로 안 만듦!

};

}

const person = createPerson("김개발", 28);

console.log(person.getName()); // "김개발"

console.log(person._name); // undefined (직접 접근 불가!)

console.log(person._ssn); // undefined (완전 은닉!)

person.setAge(-5); // 무효. age 변경 안 됨

person.setAge(29); // OK

console.log(person.getAge()); // 29

외부에서 _name, _age, _ssn 변수에 직접 접근할 방법은 절대 없다. 오직 제공된 메서드를 통해서만 조작 가능하다. 이게 바로 Java의 private + getter/setter 패턴과 동일한 효과다.

클로저는 이벤트 핸들러에서 엄청나게 자주 쓰인다. 나는 이걸 처음 발견했을 때 신세계를 경험했다.

function setupButtons() {

const buttons = document.querySelectorAll('.btn');

for (let i = 0; i < buttons.length; i++) {

const buttonIndex = i; // 각 반복마다 독립적인 변수

buttons[i].addEventListener('click', function() {

console.log(`Button ${buttonIndex} clicked`); // 클로저!

});

}

}

각 이벤트 핸들러는 자신만의 buttonIndex를 기억한다. let은 블록 스코프이기 때문에 매 반복마다 새로운 렉시컬 환경이 생성된다.

만약 let 대신 var를 썼다면?

for (var i = 0; i < buttons.length; i++) {

buttons[i].addEventListener('click', function() {

console.log(`Button ${i} clicked`); // 모두 마지막 값!

});

}

// 어떤 버튼을 눌러도 "Button 3 clicked" (buttons.length가 3이라면)

왜? var는 함수 스코프라서 i 변수가 단 하나만 존재한다. 루프가 다 돌고 나면 i는 3이 되고, 모든 핸들러는 같은 i를 참조한다.

함수형 프로그래밍을 공부하면서 클로저의 진가를 이해했다.

// 일반 함수

function multiply(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

// 커링된 함수

function curriedMultiply(a) {

return function(b) {

return a * b; // a를 클로저로 기억!

};

}

const multiplyBy3 = curriedMultiply(3); // a=3을 "고정"한 새 함수

console.log(multiplyBy3(4)); // 12

console.log(multiplyBy3(10)); // 30

const multiplyBy10 = curriedMultiply(10);

console.log(multiplyBy10(5)); // 50

실제 예시: HTTP 요청 함수

function createApiClient(baseURL, apiKey) {

// baseURL과 apiKey를 클로저로 캡처

return function(endpoint) {

return fetch(`${baseURL}${endpoint}`, {

headers: {

'Authorization': `Bearer ${apiKey}`

}

});

};

}

const githubApi = createApiClient('https://api.github.com', 'my-token-123');

githubApi('/users/codemapo').then(res => res.json());

githubApi('/repos/codemapo/blog').then(res => res.json());

baseURL과 apiKey를 매번 넘길 필요 없이, 한 번 설정하면 끝! 이게 바로 부분 적용(Partial Application)이고, Redux Thunk나 미들웨어 패턴의 핵심이다.

React를 쓰면서 가장 신기했던 건 이거다: "함수형 컴포넌트는 매번 새로 실행되는데, 어떻게 상태를 기억하지?"

답은 클로저였다.

// React의 useState 간단 구현 (개념적 모델)

const MyReact = (function() {

let hooks = []; // 모든 상태를 저장하는 배열

let currentHook = 0; // 현재 처리 중인 훅 인덱스

return {

useState(initialValue) {

const hookIndex = currentHook; // 클로저로 캡처!

// 첫 렌더링이면 초기값 설정

if (hooks[hookIndex] === undefined) {

hooks[hookIndex] = initialValue;

}

const setState = (newValue) => {

hooks[hookIndex] = newValue; // 캡처된 인덱스 사용!

render(); // 리렌더링 트리거

};

currentHook++; // 다음 훅을 위해 인덱스 증가

return [hooks[hookIndex], setState];

},

render(Component) {

currentHook = 0; // 렌더링 시작 전 인덱스 리셋

const element = Component();

return element;

}

};

})();

// 사용 예시

function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = MyReact.useState(0);

const [name, setName] = MyReact.useState("김개발");

return {

view: () => console.log(`${name}: ${count}`),

increment: () => setCount(count + 1),

changeName: (newName) => setName(newName)

};

}

const counter = MyReact.render(Counter);

counter.view(); // "김개발: 0"

counter.increment();

counter.view(); // "김개발: 1"

setState 함수는 hookIndex를 클로저로 캡처한다. 이래서 여러 개의 useState를 써도 각각 독립적으로 동작하는 것이다!

주의사항: React에서 Hook을 조건문 안에서 쓰면 안 되는 이유도 여기 있다. 인덱스가 꼬이면 엉뚱한 상태를 참조하게 된다.

비동기 함수에서 클로저는 더 중요해진다.

function fetchUserData(userId) {

const timestamp = Date.now(); // 요청 시작 시간

return fetch(`/api/users/${userId}`)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => {

const elapsed = Date.now() - timestamp; // 클로저!

console.log(`User ${userId} fetched in ${elapsed}ms`);

return data;

});

}

then 콜백은 나중에 실행되지만, timestamp와 userId를 클로저로 기억한다.

더 복잡한 예시:

function createRateLimiter(maxRequests, timeWindow) {

let requests = []; // 요청 타임스탬프 저장

return async function(fn) {

const now = Date.now();

// timeWindow 밖의 오래된 요청 제거

requests = requests.filter(time => now - time < timeWindow);

if (requests.length >= maxRequests) {

throw new Error('Rate limit exceeded');

}

requests.push(now);

return await fn(); // 실제 함수 실행

};

}

const limitedFetch = createRateLimiter(5, 60000); // 1분에 5번

// 사용

try {

await limitedFetch(() => fetch('/api/data'));

} catch (error) {

console.error(error.message);

}

requests 배열이 클로저로 유지되면서 요청 횟수를 추적한다. API 호출 제한을 구현할 때 이 패턴을 엄청 많이 쓴다.

클로저는 강력하지만, 잘못 쓰면 메모리 누수(Memory Leak)를 일으킨다. 나도 실제로 이걸로 고생한 적이 있다.

function attachHandlerBad() {

const element = document.getElementById('bigButton');

const hugeData = new Array(100000).fill('DATA'); // 큰 데이터

element.onclick = function() {

console.log(element.id); // element를 클로저로 캡처

};

// element는 onclick을 참조하고, onclick은 element를 참조

// -> 순환 참조!

}

이 코드의 문제점:

onclick 함수가 element를 클로저로 캡처element는 onclick 함수를 프로퍼티로 참조hugeData도 같은 스코프에 있어서 함께 메모리에 남음!해결책:

function attachHandlerGood() {

const element = document.getElementById('bigButton');

const elementId = element.id; // 필요한 것만 복사

element.onclick = function() {

console.log(elementId); // element 자체가 아닌 id만 캡처

};

}

React, Vue 같은 SPA를 쓸 때 컴포넌트가 언마운트되면 반드시 정리해야 한다.

class MyComponent extends React.Component {

componentDidMount() {

const handleClick = () => {

console.log(this.state.data); // this를 클로저로 캡처

};

document.addEventListener('click', handleClick);

this.cleanup = () => document.removeEventListener('click', handleClick);

}

componentWillUnmount() {

this.cleanup(); // 반드시 정리!

}

}

만약 removeEventListener를 안 하면? 컴포넌트가 사라져도 핸들러는 메모리에 남고, 그 핸들러가 참조하는 this(컴포넌트 인스턴스) 전체가 메모리에 남는다.

다행히 모던 JavaScript 엔진(V8)은 똑똑하다. 모든 변수를 다 캡처하지 않고, 실제로 사용되는 변수만 클로저에 저장한다.

function outer() {

let unused = new Array(1000000); // 사용 안 함

let used = "secret"; // 사용함

return function inner() {

console.log(used); // used만 참조

};

}

const fn = outer();

// Chrome DevTools의 Memory Profiler로 보면

// unused는 GC되고, used만 클로저에 남아있음!

V8의 Scope Analysis 덕분이다. 하지만 믿고 방심하면 안 된다. 코드를 명확하게 작성하는 게 최선이다.

클로저를 활용한 실용적인 패턴들을 정리해본다.

function once(fn) {

let executed = false;

let result;

return function(...args) {

if (!executed) {

executed = true;

result = fn.apply(this, args);

}

return result;

};

}

// 사용 예시

const initialize = once(() => {

console.log("DB 연결 시작...");

return { status: "connected" };

});

const db1 = initialize(); // "DB 연결 시작..." 출력

const db2 = initialize(); // 아무 일도 안 일어남

console.log(db1 === db2); // true (같은 객체 반환)

초기화 로직이나 결제 API처럼 중복 실행되면 안 되는 경우에 유용하다.

function memoize(fn) {

const cache = {}; // 클로저로 캐시 유지

return function(...args) {

const key = JSON.stringify(args);

if (cache[key]) {

console.log('캐시 히트!');

return cache[key];

}

console.log('계산 중...');

const result = fn.apply(this, args);

cache[key] = result;

return result;

};

}

// 피보나치 예시

const fibonacci = memoize(function(n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

return fibonacci(n - 1) + fibonacci(n - 2);

});

console.log(fibonacci(40)); // 계산 중... (느림)

console.log(fibonacci(40)); // 캐시 히트! (즉시)

Lodash의 _.memoize가 바로 이 원리다.

검색창 자동완성에서 필수적인 패턴이다.

function debounce(fn, delay) {

let timeoutId = null; // 클로저!

return function(...args) {

clearTimeout(timeoutId); // 이전 타이머 취소

timeoutId = setTimeout(() => {

fn.apply(this, args);

}, delay);

};

}

// 사용 예시

const searchAPI = (query) => {

console.log(`Searching for: ${query}`);

};

const debouncedSearch = debounce(searchAPI, 500);

// 사용자가 빠르게 타이핑

debouncedSearch('h');

debouncedSearch('he');

debouncedSearch('hel');

debouncedSearch('hell');

debouncedSearch('hello');

// 500ms 후 단 한 번만 실행: "Searching for: hello"

타이핑을 멈추고 0.5초가 지나야 API 호출이 발생한다. timeoutId를 클로저로 기억해서 이전 타이머를 취소하는 것이 핵심이다.

스크롤 이벤트 처리에 필수다.

function throttle(fn, limit) {

let inThrottle = false;

return function(...args) {

if (!inThrottle) {

fn.apply(this, args);

inThrottle = true;

setTimeout(() => {

inThrottle = false;

}, limit);

}

};

}

// 사용 예시

const handleScroll = () => {

console.log('스크롤 처리:', window.scrollY);

};

window.addEventListener('scroll', throttle(handleScroll, 200));

// 최대 초당 5번(200ms마다 1번)만 실행됨

debounce는 "마지막 것만", throttle은 "주기적으로"라는 차이가 있다.

나는 처음에 이게 헷갈렸다. 클로저와 클래스 둘 다 상태를 캡슐화할 수 있는데, 언제 뭘 써야 할까?

// 클로저 방식

function createCounter() {

let count = 0;

return {

increment: () => ++count,

decrement: () => --count,

getCount: () => count

};

}

// 클래스 방식

class Counter {

#count = 0; // Private field (ES2022)

increment() { return ++this.#count; }

decrement() { return --this.#count; }

getCount() { return this.#count; }

}

내가 정리해본 기준:

| 상황 | 추천 방식 | 이유 |

|---|---|---|

| 단순 유틸리티 함수 | 클로저 | 가볍고 빠름 |

| 객체지향 설계 | 클래스 | 상속, 명확한 구조 |

| 함수형 프로그래밍 | 클로저 | 불변성, 합성 |

| React Hooks | 클로저 | Hooks 자체가 클로저 기반 |

| 여러 인스턴스 생성 | 클래스 | 메모리 효율적 (prototype) |

내 대답: 함수가 선언될 때의 렉시컬 환경(Lexical Environment)을 기억하는 기능입니다. 함수가 자신이 태어난 스코프 밖에서 실행되더라도, 원래 스코프의 변수에 접근할 수 있습니다.

내 대답: 클로저가 참조하는 변수는 가비지 컬렉션 대상에서 제외됩니다. 함수가 살아있는 한 변수도 메모리에 계속 남기 때문에, 큰 객체를 불필요하게 참조하면 메모리 낭비가 발생합니다. 특히 DOM 요소와의 순환 참조는 치명적입니다.

내 대답: var는 함수 스코프, let은 블록 스코프입니다. 반복문에서 비동기 콜백을 만들 때 var를 쓰면 모든 콜백이 같은 변수를 참조하지만, let을 쓰면 매 반복마다 새로운 렉시컬 환경이 생성되어 각 콜백이 독립적인 값을 캡처합니다.

내 대답: useEffect 등에서 의존성 배열을 잘못 지정하면, 콜백이 오래된 렌더링의 state를 참조하는 문제입니다. 예를 들어 useEffect(() => { setInterval(() => console.log(count), 1000) }, [])는 첫 렌더링의 count만 보게 됩니다. 해결책은 올바른 의존성 배열 사용입니다.

내 대답:

null 할당으로 참조 해제클로저를 완전히 이해했다고 느낀 건 실제로 프로젝트에서 여러 번 써보고 난 후였다.

핵심만 정리해본다:

[[Environment]] 프로퍼티클로저는 자바스크립트가 함수를 일급 객체(First-Class Citizen)로 취급하기 때문에 가능한 마법이다. C나 Java 같은 언어에서는 불가능한, JavaScript만의 특권이다.

처음엔 어렵지만, 일단 와닿으면 엄청나게 강력한 도구가 된다. 나는 이제 클로저 없는 JavaScript는 상상할 수 없다.

When I first encountered closures, my brain refused to process it.

"How can a function that already finished execution still have access to its local variables?"

If you come from C or Java, this concept feels utterly wrong. In traditional compiled languages, when a function returns, its local variables are unconditionally destroyed from the stack. That's the normal lifecycle. Dead means dead.

But in JavaScript, something bizarre happens. Functions die, but their variables live on. Like zombies.

function createBankAccount(initialBalance) {

let balance = initialBalance; // Should die when function ends

return {

deposit(amount) {

balance += amount; // Wait, how is balance still alive?

return balance;

},

withdraw(amount) {

if (balance >= amount) {

balance -= amount;

return balance;

}

return "Insufficient funds";

},

getBalance() {

return balance; // Still alive!

}

};

}

const myAccount = createBankAccount(1000);

console.log(myAccount.deposit(500)); // 1500

console.log(myAccount.withdraw(200)); // 1300

console.log(myAccount.balance); // undefined (can't access directly!)

The createBankAccount function finished executing. It should be gone from the call stack. Yet somehow, balance survived. And we've achieved perfect encapsulation because myAccount.balance returns undefined — there's no way to access the variable directly.

This is closure.

I eventually understood it like this: "A function carries a birth certificate that permanently records where it was born."

To truly master closures, you must first conquer Lexical Scoping. This took me a while.

JavaScript determines a function's parent scope not by where it's called (Dynamic Scoping), but by where it's declared (Lexical Scoping).

const globalName = "Global";

function outer() {

const outerName = "Outer";

function inner() {

const innerName = "Inner";

console.log(innerName); // My own variable

console.log(outerName); // Parent's variable (KEY!)

console.log(globalName); // Grandparent's variable

}

return inner;

}

const innerFunc = outer();

innerFunc();

// "Inner"

// "Outer"

// "Global"

The critical insight: inner() can access outerName even though outer() has already returned. Why? Because inner was declared inside outer.

When a function is created, the JavaScript engine attaches a hidden property called [[Environment]] to the function object. This property points to the Lexical Environment (scope) where the function was born.

Just like humans inherit DNA from their parents, functions inherit a reference to their parent scope.

graph TD

A[Global Execution Context] --> B[outer Execution Context]

B --> C[inner Execution Context]

subgraph Global Memory

globalName

end

subgraph Outer Memory

outerName

end

subgraph Inner Memory

innerName

end

C -.->|Lookup chain| B

B -.->|Lookup chain| A

Variable lookup process:

[[Environment]]ReferenceErrorThis is the Scope Chain. Think of it as climbing your family tree.

My closure epiphany came while studying React Hooks.

function makeCounter() {

let count = 0; // This is the key

return function() {

return ++count;

};

}

const counter1 = makeCounter();

const counter2 = makeCounter();

console.log(counter1()); // 1

console.log(counter1()); // 2

console.log(counter2()); // 1 (independent!)

console.log(counter1()); // 3

Each counter has its own independent count variable. Every time you call makeCounter(), a new Lexical Environment is created, and the returned function captures that specific environment as a closure.

Suddenly it clicked. Closures aren't just "remembering variables" — they're "preserving a snapshot of the entire environment at the moment of birth."

The best analogy I found for closures is a time capsule.

You can access the environment from the moment you buried the capsule (function declaration), even when you open it much later (function execution). That's closure.

JavaScript didn't have a private keyword until ES2022's #privateField syntax. Before that, closures were the only way.

function createUser(username, email) {

let _password = null; // Private (inaccessible from outside)

let _loginAttempts = 0;

return {

getUsername() {

return username;

},

setPassword(newPassword) {

if (newPassword.length >= 8) {

_password = hashPassword(newPassword);

return true;

}

return false;

},

login(passwordAttempt) {

if (_loginAttempts >= 3) {

throw new Error("Account locked");

}

if (hashPassword(passwordAttempt) === _password) {

_loginAttempts = 0;

return "Login successful";

}

_loginAttempts++;

return "Invalid password";

}

};

}

function hashPassword(pwd) {

return pwd.split('').reverse().join(''); // Dummy hash

}

const user = createUser("codemapo", "dev@example.com");

user.setPassword("strongpass123");

console.log(user.login("wrongpass")); // "Invalid password"

console.log(user.login("strongpass123")); // "Login successful"

console.log(user._password); // undefined (totally hidden!)

There is absolutely no way to access _password or _loginAttempts from outside. Only through the provided methods. This is identical to Java's private + getter/setter pattern.

Closures are everywhere in event handlers. This was a revelation for me.

function attachButtonHandlers() {

const colors = ['red', 'blue', 'green'];

colors.forEach((color, index) => {

const button = document.getElementById(`btn-${index}`);

button.addEventListener('click', function() {

// Closure captures both 'color' and 'index'

console.log(`Button ${index}: ${color}`);

this.style.backgroundColor = color;

});

});

}

Each event handler remembers its own color and index. Since forEach creates a new scope for each iteration, every callback gets its own lexical environment.

Classic mistake with var:

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i); // All print "3"

}, 1000);

}

Why? var has function scope, so there's only one i variable. By the time the timeouts fire, the loop has finished and i is 3.

Fix with let:

for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i); // Prints 0, 1, 2

}, 1000);

}

let has block scope, so each iteration creates a new i.

Functional programming taught me the true power of closures.

// Regular function

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

// Curried function

function curriedAdd(a) {

return function(b) {

return a + b; // 'a' is captured in closure

};

}

const add5 = curriedAdd(5); // "Lock in" a=5

console.log(add5(3)); // 8

console.log(add5(10)); // 15

Real-world example: HTTP client factory

function createHttpClient(baseURL, authToken) {

// Capture baseURL and authToken in closure

return async function(endpoint, options = {}) {

const response = await fetch(`${baseURL}${endpoint}`, {

...options,

headers: {

'Authorization': `Bearer ${authToken}`,

...options.headers

}

});

return response.json();

};

}

const githubAPI = createHttpClient(

'https://api.github.com',

'ghp_your_token_here'

);

// Now you don't need to pass baseURL and token every time!

const userData = await githubAPI('/users/codemapo');

const repos = await githubAPI('/users/codemapo/repos');

This is partial application — the foundation of Redux middleware and functional composition.

The most mind-blowing thing about React: "Functional components re-execute on every render, yet they remember state. How?"

The answer: closures.

// Simplified useState implementation (conceptual model)

const MyReact = (function() {

let hooks = []; // State storage (closure!)

let currentHook = 0; // Current hook index

return {

useState(initialValue) {

const hookIndex = currentHook; // Captured in closure!

if (hooks[hookIndex] === undefined) {

hooks[hookIndex] = initialValue;

}

const setState = (newValue) => {

hooks[hookIndex] = newValue; // Uses captured index!

render(); // Trigger re-render

};

currentHook++;

return [hooks[hookIndex], setState];

},

render(Component) {

currentHook = 0; // Reset index before render

const instance = Component();

return instance;

}

};

})();

// Usage

function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = MyReact.useState(0);

const [name, setName] = MyReact.useState("Developer");

return {

display: () => console.log(`${name}: ${count}`),

increment: () => setCount(count + 1)

};

}

const app = MyReact.render(Counter);

app.display(); // "Developer: 0"

app.increment();

app.display(); // "Developer: 1"

The setState function captures hookIndex in a closure. That's why multiple useState calls work independently!

Important: This is why you can't use Hooks conditionally in React — it would mess up the index order.

Closures become even more critical in asynchronous code.

function trackAPICall(endpoint) {

const startTime = Date.now();

return fetch(endpoint)

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => {

const duration = Date.now() - startTime; // Closure!

console.log(`${endpoint} took ${duration}ms`);

return data;

});

}

The .then() callback executes later, but it remembers startTime and endpoint via closure.

More complex example: Rate limiter

function createRateLimiter(maxCalls, timeWindow) {

let callTimestamps = []; // Captured in closure

return async function(apiCall) {

const now = Date.now();

// Remove old timestamps outside the window

callTimestamps = callTimestamps.filter(

timestamp => now - timestamp < timeWindow

);

if (callTimestamps.length >= maxCalls) {

throw new Error(`Rate limit: max ${maxCalls} calls per ${timeWindow}ms`);

}

callTimestamps.push(now);

return await apiCall();

};

}

const limitedFetch = createRateLimiter(5, 60000); // 5 calls per minute

try {

await limitedFetch(() => fetch('/api/data'));

} catch (error) {

console.error(error.message);

}

The callTimestamps array persists across invocations via closure, tracking request frequency. This pattern is essential for API rate limiting.

Closures are powerful but dangerous. I learned this the hard way in production.

function attachHandlerBad() {

const element = document.getElementById('myButton');

const largeData = new Array(1000000).fill('DATA'); // Huge array

element.onclick = function() {

console.log(element.id); // Captures 'element'

};

// element -> onclick -> element (circular!)

// largeData also captured unnecessarily!

}

Problems:

onclick function captures element in closureelement references the onclick function as a propertylargeData is in the same scope, so it's also retained!Solution:

function attachHandlerGood() {

const element = document.getElementById('myButton');

const elementId = element.id; // Extract only what you need

element.onclick = function() {

console.log(elementId); // Captures primitive, not the DOM element

};

}

In React, Vue, or any SPA, you must clean up when components unmount.

function ChatComponent() {

useEffect(() => {

const handleMessage = (event) => {

console.log('Message:', event.data);

// This closure captures component state/props!

};

window.addEventListener('message', handleMessage);

return () => {

window.removeEventListener('message', handleMessage); // CRITICAL!

};

}, []);

}

If you forget removeEventListener, the handler stays in memory even after the component unmounts, keeping the entire component instance alive.

Fortunately, modern JavaScript engines (V8, SpiderMonkey) are smart. They don't capture all variables — only the ones actually used.

function outer() {

let unused = new Array(10000000); // Not used

let used = "secret"; // Used

return function inner() {

console.log(used); // Only references 'used'

};

}

const fn = outer();

// Check Chrome DevTools Memory Profiler:

// 'unused' is GC'd, only 'used' remains in closure!

This is V8's Scope Analysis at work. But don't rely on it blindly — write clean code.

Here are practical closure-based patterns I use constantly.

function once(fn) {

let executed = false;

let result;

return function(...args) {

if (!executed) {

executed = true;

result = fn.apply(this, args);

}

return result;

};

}

// Usage

const initDB = once(() => {

console.log("Connecting to database...");

return { connection: "active" };

});

const db1 = initDB(); // "Connecting to database..."

const db2 = initDB(); // Silent

console.log(db1 === db2); // true (same object returned)

Perfect for initialization logic or payment APIs where duplicate execution is dangerous.

function memoize(fn) {

const cache = {}; // Persists via closure

return function(...args) {

const key = JSON.stringify(args);

if (cache[key] !== undefined) {

console.log('Cache hit!');

return cache[key];

}

console.log('Computing...');

const result = fn.apply(this, args);

cache[key] = result;

return result;

};

}

// Fibonacci example

const fib = memoize(function(n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

});

console.log(fib(40)); // Computing... (slow)

console.log(fib(40)); // Cache hit! (instant)

This is the core of Lodash's _.memoize.

Essential for search input autocomplete.

function debounce(fn, delay) {

let timeoutId; // Captured in closure

return function(...args) {

clearTimeout(timeoutId);

timeoutId = setTimeout(() => {

fn.apply(this, args);

}, delay);

};

}

// Usage

const search = (query) => {

console.log(`Searching for: ${query}`);

};

const debouncedSearch = debounce(search, 300);

// User types fast

debouncedSearch('j');

debouncedSearch('ja');

debouncedSearch('jav');

debouncedSearch('java');

debouncedSearch('javas');

debouncedSearch('javasc');

debouncedSearch('javascript');

// Only one API call after 300ms: "Searching for: javascript"

The timeoutId persists in the closure, allowing us to cancel previous timers.

Critical for scroll event handling.

function throttle(fn, limit) {

let inThrottle = false;

return function(...args) {

if (!inThrottle) {

fn.apply(this, args);

inThrottle = true;

setTimeout(() => {

inThrottle = false;

}, limit);

}

};

}

// Usage

const logScroll = () => {

console.log('Scroll position:', window.scrollY);

};

window.addEventListener('scroll', throttle(logScroll, 200));

// Maximum 5 times per second (once every 200ms)

Difference: debounce waits for a pause, throttle executes at regular intervals.

Creating nested functions isn't free.

Every time you create a function inside another function, you're allocating a new object.

// BAD: Creates new function on every render

function BadComponent() {

return (

<button onClick={() => console.log('Clicked')}>

Click me

</button>

);

}

// GOOD: Reuses the same function

function GoodComponent() {

const handleClick = useCallback(() => {

console.log('Clicked');

}, []);

return <button onClick={handleClick}>Click me</button>;

}

Accessing variables up the scope chain is slower than local variables.

function outer() {

const data = { value: 42 };

return function inner() {

// Scope chain lookup: inner -> outer -> global

console.log(data.value);

};

}

// vs.

function optimized() {

const value = 42; // Direct local access

return function() {

console.log(value);

};

}

Modern engines optimize this, but awareness helps in performance-critical code.

Large closures prevent garbage collection. If you have huge data structures, be careful.

function processData() {

const hugeArray = new Array(10000000).fill('data');

// Only use what you need

const summary = hugeArray.length;

return function() {

console.log(summary); // Only captures 'summary', not 'hugeArray'

// (if V8's scope analysis works correctly)

};

}

My answer: A closure is the combination of a function and its lexical environment. It allows a function to access variables from its parent scope, even after the parent function has returned.

My answer: Variables referenced by closures are excluded from garbage collection. As long as the closure exists, those variables remain in memory. If you capture large objects unintentionally (like DOM elements or big arrays), memory usage grows. Circular references between closures and DOM elements are especially problematic.

My answer: var has function scope, creating a single variable shared across iterations. let has block scope, creating a new variable binding for each iteration. In loops with async callbacks, var causes all callbacks to share the final value, while let gives each callback its own value.

My answer: A stale closure occurs when a function (like in useEffect) captures state/props from a previous render. For example, useEffect(() => { setInterval(() => console.log(count), 1000) }, []) captures count from the first render and never updates. The fix is proper dependency arrays.

My answer:

useCallback in React to prevent recreating functions