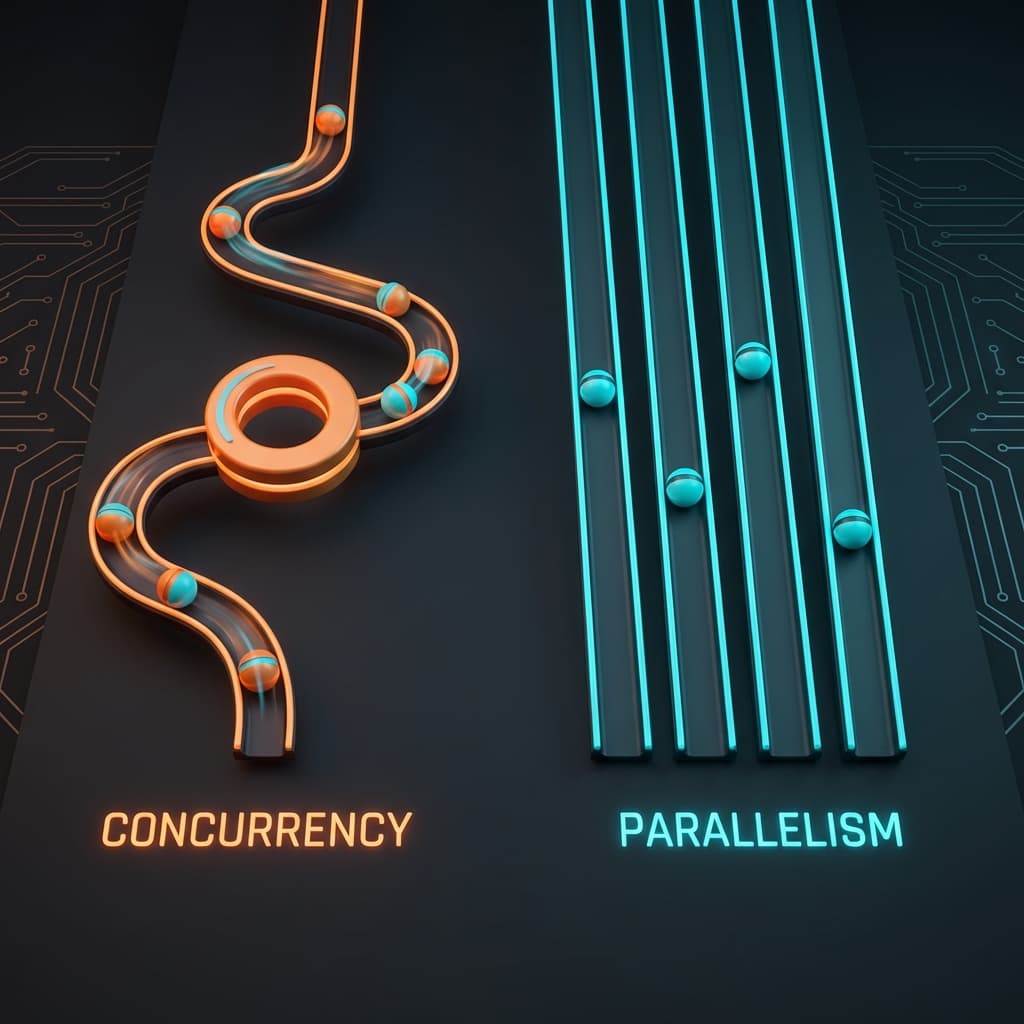

동시성(Concurrency)과 병렬성(Parallelism): 헷갈리지 말자 (대규모 업데이트)

요리사 한 명이 멀티태스킹을 하는 것과 요리사 두 명이 일하는 것의 차이. 스레드, 프로세스, 그리고 Python의 GIL 문제까지.

요리사 한 명이 멀티태스킹을 하는 것과 요리사 두 명이 일하는 것의 차이. 스레드, 프로세스, 그리고 Python의 GIL 문제까지.

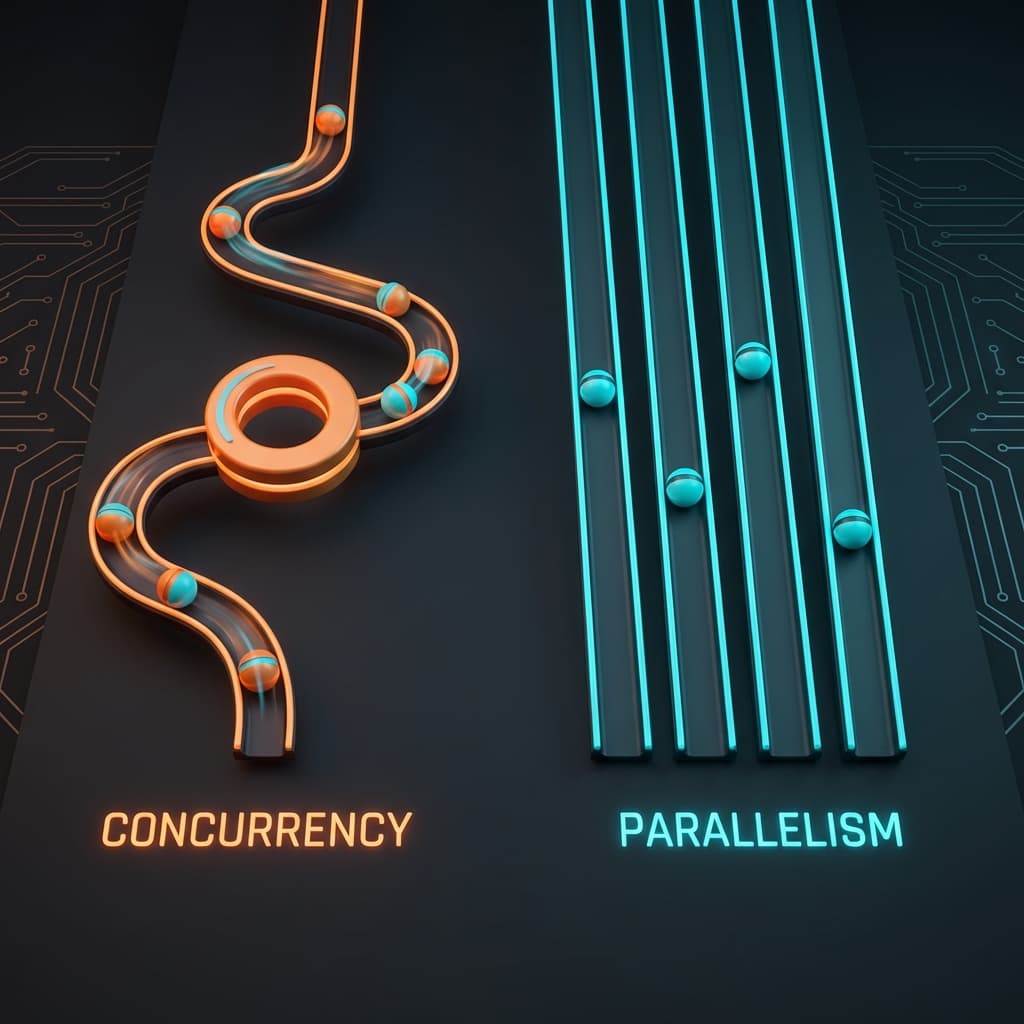

내 서버는 왜 걸핏하면 뻗을까? OS가 한정된 메모리를 쪼개 쓰는 처절한 사투. 단편화(Fragmentation)와의 전쟁.

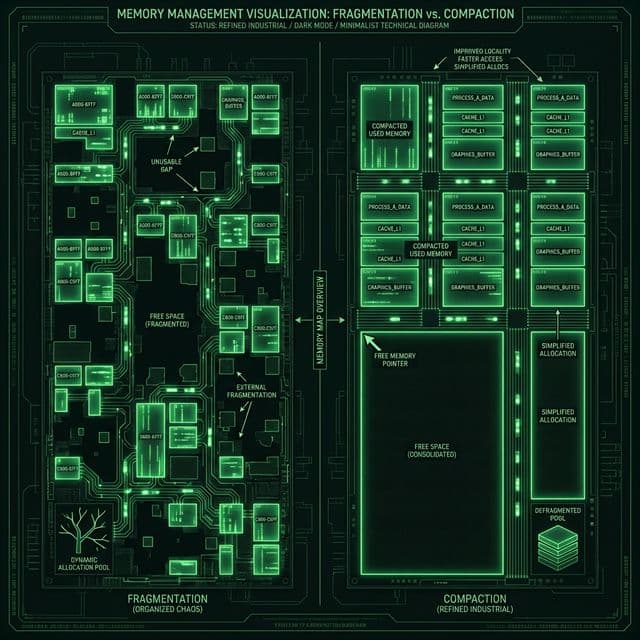

미로를 탈출하는 두 가지 방법. 넓게 퍼져나갈 것인가(BFS), 한 우물만 팔 것인가(DFS). 최단 경로는 누가 찾을까?

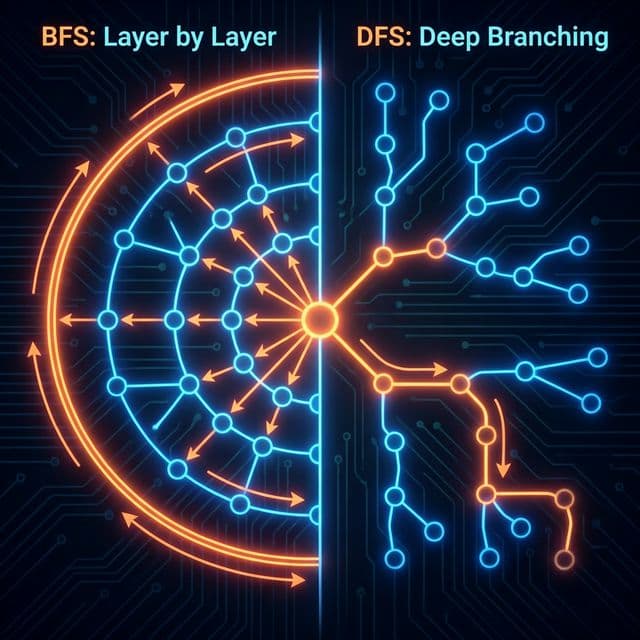

이름부터 빠릅니다. 피벗(Pivot)을 기준으로 나누고 또 나누는 분할 정복 알고리즘. 왜 최악엔 느린데도 가장 많이 쓰일까요?

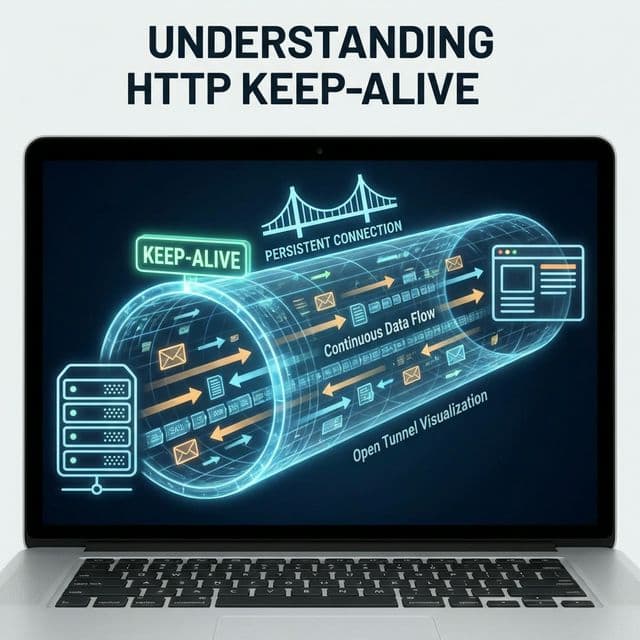

매번 3-Way Handshake 하느라 지쳤나요? 한 번 맺은 인연(TCP 연결)을 소중히 유지하는 법. HTTP 최적화의 기본.

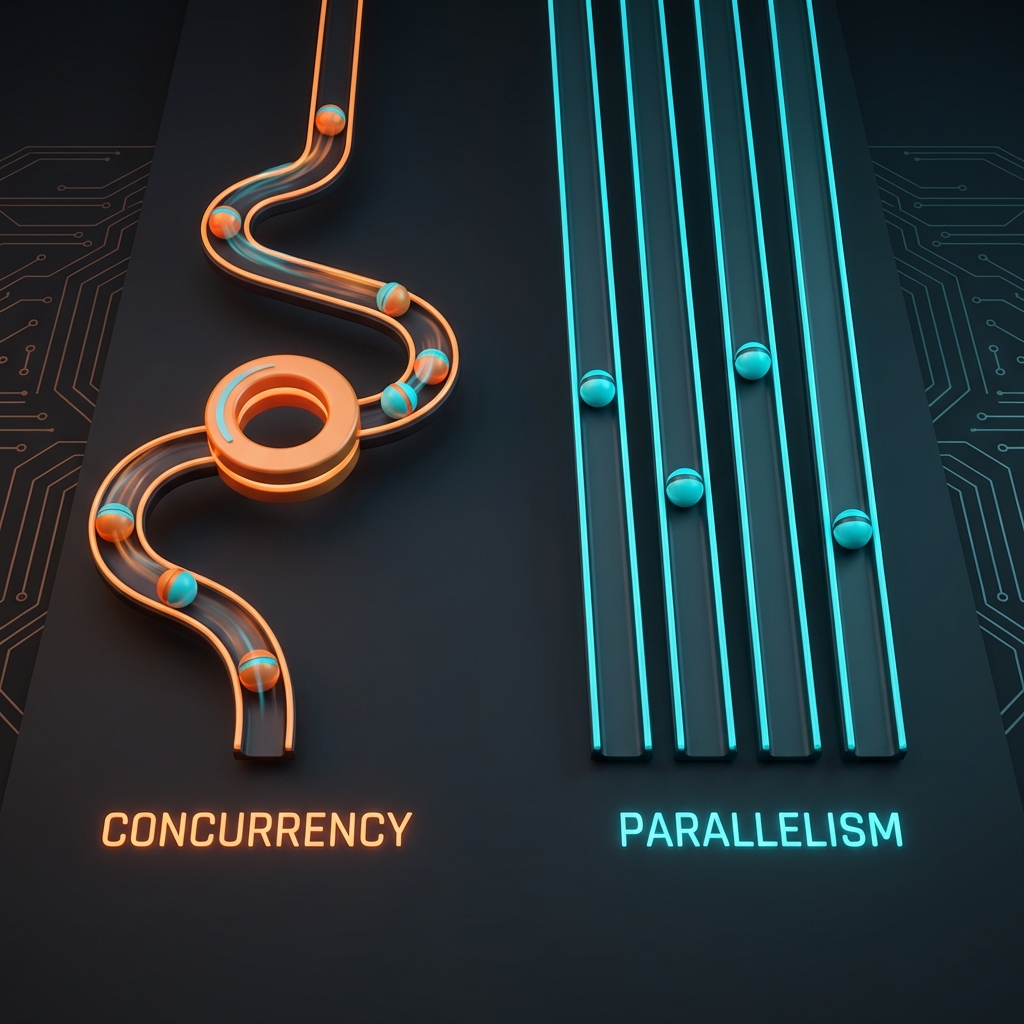

처음 이 개념을 접했을 때, 나는 완전히 헷갈렸다. "동시성(Concurrency)과 병렬성(Parallelism)의 차이가 뭔가요?"라는 질문을 처음 들었을 때, 나는 "둘 다 여러 작업을 동시에 처리하는 건데... 뭐가 다르지?"라고 생각했다. 그냥 같은 말을 영어로 다르게 표현한 거 아닌가? 시니어 개발자는 웃으면서 이렇게 비유했다.

"밥 먹으면서 TV 보는 거랑, 너는 밥 먹고 너의 친구는 TV 틀어주는 거랑 뭐가 다른 것 같아?"

순간 머릿속이 하얘졌다. 결과적으로는 둘 다 '밥도 먹고 TV도 보는' 상황이지만, 실행 방식이 완전히 다르다. 전자는 내가 혼자서 시선을 번갈아 가며 멀티태스킹하는 것이고, 후자는 물리적으로 두 명이 각자 일을 분담하는 것이다.

그날 이후 나는 이 개념을 완전히 이해했다. 동시성은 구조적인 것이고, 병렬성은 실행적인 것이다. 이 글에서는 내가 몇 년간 실제로 겪으며 받아들였던 개념들을 정리해본다.

스타트업 초기, 우리는 대량의 API 호출을 처리해야 했다. 수천 개의 사용자 데이터를 외부 API로 동기화하는 작업이었는데, 순차적으로 처리하니 끔찍하게 느렸다. 당연히 멀티스레딩을 도입했다.

import threading

import time

def fetch_user_data(user_id):

# 외부 API 호출 시뮬레이션

time.sleep(0.5) # 실제로는 requests.get()

return f"User {user_id} data"

# 10명의 사용자 데이터를 가져오기

start = time.time()

threads = []

for i in range(10):

t = threading.Thread(target=fetch_user_data, args=(i,))

threads.append(t)

t.start()

for t in threads:

t.join()

print(f"Time taken: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

# 기대 - 0.5초 (병렬 실행)

# 실제 - 0.5초 (I/O bound라서 다행히 빠름)

이건 다행히 빨랐다. I/O 작업(네트워크 대기)이었기 때문이다. 하지만 다음 프로젝트에서 CPU intensive한 작업(이미지 리사이징)을 시도했을 때 문제가 터졌다.

import threading

import time

def heavy_computation(n):

# CPU 집약적 작업 (예: 이미지 처리)

result = 0

for i in range(n):

result += i ** 2

return result

# 단일 스레드

start = time.time()

for i in range(4):

heavy_computation(10000000)

print(f"Single thread: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

# 결과 - 약 2.5초

# 멀티 스레드 (4개)

start = time.time()

threads = []

for i in range(4):

t = threading.Thread(target=heavy_computation, args=(10000000,))

threads.append(t)

t.start()

for t in threads:

t.join()

print(f"Multi thread: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

# 기대 - 0.625초 (4배 빠름)

# 실제 - 2.5초 (똑같음! 뭐지?)

충격이었다. 스레드를 4개 만들었는데 속도가 똑같다니? CPU 사용률을 보니 코어 하나만 100%였고 나머지는 놀고 있었다. 구글링 끝에 드디어 만난 단어, GIL (Global Interpreter Lock).

Python의 CPython 구현체는 메모리 관리(Reference Counting)의 안전성을 위해 한 번에 하나의 스레드만 Python 바이트코드를 실행하도록 제한한다. 멀티 코어가 100개 있어도 소용없다. 파이썬 인터프리터 레벨에서 줄을 세워놨기 때문이다.

sequenceDiagram

participant T1 as Thread 1

participant GIL as Global Interpreter Lock

participant T2 as Thread 2

T1->>GIL: Acquire Lock

T1->>T1: Execute Python Code

T1->>GIL: Release Lock (I/O Wait or Tick)

T2->>GIL: Acquire Lock

T2->>T2: Execute Python Code

T2->>GIL: Release Lock

이 다이어그램을 보는 순간 모든 게 와닿았다. 파이썬 스레드는 동시성(Concurrency)은 제공하지만 병렬성(Parallelism)은 제공하지 않는다. 시분할로 빠르게 스위칭은 하지만, 실제로 물리적으로 동시에 실행되지는 않는다.

해결책은 multiprocessing 모듈이었다. 스레드가 아니라 프로세스를 여러 개 띄우면 각각 독립된 인터프리터와 메모리를 가지므로 GIL 영향을 받지 않는다.

from multiprocessing import Process, Pool

import time

def heavy_computation(n):

result = 0

for i in range(n):

result += i ** 2

return result

if __name__ == '__main__':

# 멀티 프로세싱 (4개)

start = time.time()

with Pool(4) as p:

results = p.map(heavy_computation, [10000000] * 4)

print(f"Multi process: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

# 결과: 약 0.7초 (3.5배 빠름!)

드디어 진짜 병렬 처리가 작동했다. CPU 사용률을 보니 4개 코어가 모두 100%로 돌아갔다. 이때 나는 결국 이거였다는 걸 깨달았다. 동시성은 논리적 개념이고, 병렬성은 물리적 개념이다.

싱글 코어 CPU에서 어떻게 여러 프로그램이 동시에 돌아가는 것처럼 보일까? 비밀은 컨텍스트 스위칭(Context Switching)과 시분할(Time Slicing)에 있다.

OS 스케줄러는 매우 짧은 시간(보통 10ms)마다 실행 중인 프로세스/스레드를 교체한다.

우리 눈에는 끊김 없이 보이지만(초당 100번 스위칭), 실제로는 매우 빠르게 돌아가며 실행하는 것이다.

컨텍스트 스위칭은 공짜가 아니다. 상태를 저장하고 복구하는 과정에서 다음 비용이 발생한다.

그래서 스레드를 무한정 늘린다고 빨라지는 게 아니다. 오히려 스레드가 너무 많으면 CPU가 실제 작업은 안 하고 스위칭만 하느라 바빠진다. 이게 바로 C10K 문제의 핵심이었다.

Node.js를 처음 봤을 때 이해가 안 갔다. "싱글 스레드인데 어떻게 수천 명의 동시 접속을 처리하죠?" 답은 이벤트 루프(Event Loop)와 Non-blocking I/O에 있다.

const fs = require('fs');

console.log('1. Start');

// 비동기 파일 읽기

fs.readFile('bigfile.txt', 'utf8', (err, data) => {

console.log('3. File read complete');

});

console.log('2. Continue execution');

// 출력 순서:

// 1. Start

// 2. Continue execution

// 3. File read complete (나중에)

fs.readFile()을 호출하는 순간, Node.js는 파일 읽기 요청을 OS 커널(또는 libuv 스레드 풀)에 던지고 즉시 다음 코드로 넘어간다. 파일 읽기가 완료되면 이벤트 루프가 콜백을 큐에 넣어 나중에 실행한다.

현대 JavaScript는 더 나아가 async/await를 통해 비동기 코드를 동기 코드처럼 작성할 수 있게 해준다.

async function fetchMultipleUsers() {

console.log('Start fetching');

// 병렬로 3개 요청 동시 발송

const promises = [

fetch('https://api.example.com/user/1'),

fetch('https://api.example.com/user/2'),

fetch('https://api.example.com/user/3')

];

const results = await Promise.all(promises);

console.log('All done');

return results;

}

await를 만나는 순간 함수는 일시 정지되고, 이벤트 루프는 다른 작업을 처리한다. 프로미스가 resolve되면 함수는 멈춘 지점부터 재개된다. 이건 협력적 멀티태스킹(Cooperative Multitasking)의 완벽한 예시다. 스레드 블로킹 없이 동시성을 달성한다.

Python과 Node.js를 거쳐 Go를 만났을 때, 나는 드디어 이상적인 동시성 모델을 찾았다고 느꼈다. Goroutine은 경량 스레드로, 메모리 소비가 겨우 2KB다. (OS 스레드는 1MB)

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func task(id int) {

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

fmt.Printf("Task %d done\n", id)

}

func main() {

// 1만 개의 고루틴 생성 (쉽게 가능!)

for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ {

go task(i)

}

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

fmt.Println("All tasks launched")

}

이 코드는 실제로 작동한다. 1만 개의 고루틴을 만들어도 메모리는 20MB밖에 안 쓴다. OS 스레드로 했다면 10GB가 필요했을 것이다.

Go 런타임은 M:N 스케줄링을 사용한다. M개의 OS 스레드 위에 N개의 고루틴을 매핑한다. 고루틴 하나가 블로킹 I/O를 만나면, Go 스케줄러는 그 OS 스레드를 블로킹하지 않고 다른 고루틴으로 스위칭한다.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

ch := make(chan int)

// Producer 고루틴

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

for i := 0; i < 100; i++ {

ch <- i

}

close(ch)

}()

// Consumer 고루틴 (3개)

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(workerID int) {

defer wg.Done()

for num := range ch {

fmt.Printf("Worker %d processed %d\n", workerID, num)

}

}(i)

}

wg.Wait()

}

이 패턴이 너무 강력해서 Java도 JDK 21에서 Virtual Threads (Project Loom)로 비슷한 모델을 도입했다.

1999년, 댄 Kegel은 충격적인 문제를 제기했다. "서버 한 대가 어떻게 동시에 1만 개의 클라이언트 연결을 유지할 수 있을까?"

당시 주류 방식은 Thread-per-Connection이었다. 클라이언트 하나당 스레드 하나. 문제는 스레드 1개당 메모리가 약 1MB라는 것이다. 1만 개 연결 = 10GB 메모리. 당시 서버로는 감당 불가능했다.

Linux의 epoll (또는 BSD의 kqueue)은 단 하나의 스레드로 수만 개의 소켓을 감시할 수 있다.

// 의사 코드

int epoll_fd = epoll_create1(0);

// 1만 개의 소켓을 epoll에 등록

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

struct epoll_event ev;

ev.events = EPOLLIN;

ev.data.fd = client_sockets[i];

epoll_ctl(epoll_fd, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, client_sockets[i], &ev);

}

// 이벤트 루프

while (1) {

int n = epoll_wait(epoll_fd, events, MAX_EVENTS, -1);

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

if (events[i].events & EPOLLIN) {

// 3번 소켓에 데이터 도착! 처리하자

handle_read(events[i].data.fd);

}

}

}

이게 바로 Reactor 패턴이자 Node.js, Nginx, Redis의 핵심 아키텍처다. 스레드 수를 늘리지 않고 동시 연결 수만 늘린다. 이건 순수한 동시성이지 병렬성이 아니다. 그런데 I/O bound 작업에서는 이게 더 빠르다.

"락(Lock) 잡고 데드락 걱정하는 게 너무 싫다!" 그래서 나온 것이 Actor Model이다. Erlang, Elixir, Akka가 이 모델을 사용한다.

# Elixir 예제

defmodule Counter do

def start_link(initial_value) do

spawn(fn -> loop(initial_value) end)

end

defp loop(current_value) do

receive do

{:increment, caller} ->

new_value = current_value + 1

send(caller, {:ok, new_value})

loop(new_value)

{:get, caller} ->

send(caller, {:ok, current_value})

loop(current_value)

end

end

end

# 사용

counter = Counter.start_link(0)

send(counter, {:increment, self()})

receive do

{:ok, value} -> IO.puts("New value: #{value}")

end

액터는 자기만의 상태(current_value)를 가지고 있고, 다른 액터는 절대 그 메모리에 접근하지 못한다. 락이 필요 없으니 데드락도 없다. 이 모델은 통신 시스템에서 특히 강력하다. (WhatsApp은 초창기 Erlang으로 9억 명을 지원했다)

내가 정리한 답: 프로세스는 '집'이고 스레드는 '방'이다.

함수 호출 관점이다.

result = fetch_data()fetch_data().then(result => ...)여러 스레드가 count++ 같은 공유 변수에 동시 접근할 때 발생한다.

해결법:

AtomicInteger in Java)JS 코드 실행 스레드는 하나지만, 파일 I/O, 암호화, DNS 같은 무거운 작업은 libuv가 내부적으로 스레드 풀을 사용해 병렬 처리한다. 즉, JS 엔진은 싱글 스레드지만 전체 시스템은 멀티 스레드다.

multiprocessing 모듈 사용 (프로세스 생성)asyncio 사용 (이벤트 루프)몇 년간의 삽질 끝에 나는 다음을 완전히 이해했다.

결국 이거였다. 동시성과 병렬성은 둘 다 중요하지만, 문제의 성격(I/O vs CPU)에 따라 올바른 도구를 선택하는 게 핵심이다. 무조건 스레드 많이 만든다고, 코어 많이 쓴다고 빨라지는 게 아니다. 컨텍스트를 이해하고 적재적소에 쓰는 게 진짜 실력이다.

When I first encountered this question — "What's the difference between Concurrency and Parallelism?" — I froze. Aren't they both about doing multiple things at once? I stumbled through an answer about threads and cores, but the senior developer smiled and said:

"Think of it this way. You're eating lunch while watching TV. That's one scenario. Now imagine you're eating lunch while your friend operates the TV remote for you. What's different?"

That simple analogy changed everything. In both cases, you're eating and watching TV. But in the first scenario, you're rapidly context-switching — taking a bite, glancing at the screen, taking another bite. In the second, there are literally two people executing tasks simultaneously.

That's when it clicked. Concurrency is about structure (how you design your program to handle multiple tasks). Parallelism is about execution (whether tasks physically run at the same instant).

Early in my startup journey, we needed to process thousands of API calls. Syncing user data with external services was painfully slow when done sequentially. Naturally, I reached for multithreading.

import threading

import time

def fetch_user_data(user_id):

# Simulating external API call

time.sleep(0.5) # In reality: requests.get()

return f"User {user_id} data"

# Fetch data for 10 users

start = time.time()

threads = []

for i in range(10):

t = threading.Thread(target=fetch_user_data, args=(i,))

threads.append(t)

t.start()

for t in threads:

t.join()

print(f"Time taken: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

# Expected: 0.5s (parallel execution)

# Actual: 0.5s (works great for I/O bound!)

This worked beautifully because it was I/O-bound (waiting for network responses). But when I tried the same approach for CPU-intensive work (image resizing), disaster struck.

import threading

import time

def heavy_computation(n):

# CPU-intensive work (e.g., image processing)

result = 0

for i in range(n):

result += i ** 2

return result

# Single thread

start = time.time()

for i in range(4):

heavy_computation(10000000)

print(f"Single thread: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

# Result: ~2.5 seconds

# Multi-threaded (4 threads)

start = time.time()

threads = []

for i in range(4):

t = threading.Thread(target=heavy_computation, args=(10000000,))

threads.append(t)

t.start()

for t in threads:

t.join()

print(f"Multi-threaded: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

# Expected: ~0.625s (4x faster)

# Actual: ~2.5s (exactly the same! WTF?)

I was floored. Four threads, same execution time. Checking CPU usage revealed only one core maxed out at 100% while the others sat idle. Hours of Googling led me to three dreaded letters: GIL.

Python's CPython implementation uses a Global Interpreter Lock to ensure thread-safe memory management (reference counting). Only one thread can execute Python bytecode at a time, regardless of how many cores you have.

sequenceDiagram

participant T1 as Thread 1

participant GIL as Global Interpreter Lock

participant T2 as Thread 2

T1->>GIL: Acquire Lock

T1->>T1: Execute Python Code

T1->>GIL: Release Lock (I/O Wait or Tick)

T2->>GIL: Acquire Lock

T2->>T2: Execute Python Code

T2->>GIL: Release Lock

This diagram was my eureka moment. Python threads provide concurrency (they can exist simultaneously and take turns), but not parallelism (they don't execute simultaneously). The threads context-switch rapidly, but only one runs at any instant.

The solution was switching from threading to multiprocessing. Separate processes have independent interpreters and memory spaces, bypassing the GIL entirely.

from multiprocessing import Pool

import time

def heavy_computation(n):

result = 0

for i in range(n):

result += i ** 2

return result

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Multiprocessing (4 processes)

start = time.time()

with Pool(4) as p:

results = p.map(heavy_computation, [10000000] * 4)

print(f"Multi-process: {time.time() - start:.2f}s")

# Result: ~0.7s (3.5x speedup!)

Finally, true parallelism. All four cores hit 100% utilization. This experience hammered home the distinction: concurrency is logical, parallelism is physical.

How does a single-core CPU run multiple programs seemingly at once? Through Context Switching and Time Slicing.

The OS scheduler switches between processes/threads every few milliseconds:

We perceive continuity because switches happen 100+ times per second. But there's a cost.

Context switching isn't free. Each switch incurs:

This is why spawning thousands of threads doesn't make your program faster. Beyond a certain point, the CPU spends more time switching than doing actual work. This was the core insight behind the C10K problem.

When I first learned Node.js was single-threaded, I was skeptical. "How can it handle thousands of concurrent connections?" The answer lies in the Event Loop and Non-blocking I/O.

const fs = require('fs');

console.log('1. Start');

// Asynchronous file read

fs.readFile('bigfile.txt', 'utf8', (err, data) => {

console.log('3. File read complete');

});

console.log('2. Continue execution');

// Output order:

// 1. Start

// 2. Continue execution

// 3. File read complete (later)

When fs.readFile() executes, Node.js delegates the I/O to the OS kernel (or libuv thread pool) and immediately continues. When the file read completes, the event loop invokes the callback.

Modern JavaScript makes this even cleaner with async/await syntax.

async function fetchMultipleUsers() {

console.log('Start fetching');

// Launch 3 requests in parallel

const promises = [

fetch('https://api.example.com/user/1'),

fetch('https://api.example.com/user/2'),

fetch('https://api.example.com/user/3')

];

const results = await Promise.all(promises);

console.log('All done');

return results;

}

When the function hits await, it pauses (yields control), allowing the event loop to handle other tasks. When the promises resolve, execution resumes from that exact point. This is cooperative multitasking at its finest — achieving concurrency without thread blocking.

After wrestling with Python's GIL and JavaScript's callback hell, discovering Go felt like finding the promised land. Goroutines are lightweight threads consuming only ~2KB of memory each (OS threads consume ~1MB).

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func task(id int) {

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

fmt.Printf("Task %d done\n", id)

}

func main() {

// Spawn 10,000 goroutines (easily!)

for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ {

go task(i)

}

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

fmt.Println("All tasks launched")

}

This actually works. 10,000 goroutines consume only ~20MB. Doing this with OS threads would require 10GB of memory.

Go uses M:N scheduling — mapping N goroutines onto M OS threads. When a goroutine blocks on I/O, the Go scheduler doesn't block the underlying OS thread. It switches to another runnable goroutine.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sync"

)

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

ch := make(chan int)

// Producer goroutine

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

defer wg.Done()

for i := 0; i < 100; i++ {

ch <- i

}

close(ch)

}()

// Consumer goroutines (3 workers)

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

wg.Add(1)

go func(workerID int) {

defer wg.Done()

for num := range ch {

fmt.Printf("Worker %d processed %d\n", workerID, num)

}

}(i)

}

wg.Wait()

}

This pattern is so powerful that Java adopted a similar model in JDK 21 with Virtual Threads (Project Loom).

In 1999, Dan Kegel posed a provocative question: "How can a server handle 10,000 concurrent client connections?"

The prevailing approach was Thread-per-Connection — spawn a thread for each client. Problem: each thread consumes ~1MB of memory. 10,000 connections = 10GB memory. Servers of that era couldn't handle it.

Linux's epoll (or BSD's kqueue) allows a single thread to monitor tens of thousands of sockets.

// Pseudocode

int epoll_fd = epoll_create1(0);

// Register 10,000 sockets with epoll

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; i++) {

struct epoll_event ev;

ev.events = EPOLLIN;

ev.data.fd = client_sockets[i];

epoll_ctl(epoll_fd, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, client_sockets[i], &ev);

}

// Event loop

while (1) {

int n = epoll_wait(epoll_fd, events, MAX_EVENTS, -1);

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++) {

if (events[i].events & EPOLLIN) {

// Socket #3 has data! Handle it

handle_read(events[i].data.fd);

}

}

}

This is the Reactor Pattern — the core architecture of Node.js, Nginx, and Redis. It's pure concurrency without parallelism. Yet for I/O-bound workloads, it outperforms multi-threaded blocking servers.

"I'm tired of wrestling with locks and deadlocks!" That's why the Actor Model exists. Erlang, Elixir, and Akka embrace this paradigm.

# Elixir example

defmodule Counter do

def start_link(initial_value) do

spawn(fn -> loop(initial_value) end)

end

defp loop(current_value) do

receive do

{:increment, caller} ->

new_value = current_value + 1

send(caller, {:ok, new_value})

loop(new_value)

{:get, caller} ->

send(caller, {:ok, current_value})

loop(current_value)

end

end

end

# Usage

counter = Counter.start_link(0)

send(counter, {:increment, self()})

receive do

{:ok, value} -> IO.puts("New value: #{value}")

end

Each actor owns its state (current_value). No other actor can directly access that memory. No locks needed, no deadlocks possible. WhatsApp famously supported 900 million users using Erlang's actor model.

My mental model: A process is a house, threads are rooms.

Function invocation perspective:

result = fetch_data()fetch_data().then(result => ...)Multiple threads accessing shared variables like count++ simultaneously.

Solutions:

AtomicInteger)The JS execution thread is single-threaded, but Node.js delegates heavy operations (file I/O, crypto, DNS) to libuv, which uses a thread pool under the hood. The JS engine is single-threaded, but the overall system is multi-threaded.

multiprocessing (spawn processes)asyncio (event loop)