SSL/TLS 인증서: 인터넷 신분증과 암호화의 모든 것 (완전정복)

Netscape의 SSL부터 최신 TLS 1.3까지. 대칭키/비대칭키 암호화의 조화, Handshake 과정 상세 분석(1.2 vs 1.3), CA 신뢰 사슬, 그리고 HTTPS의 동작 원리를 파헤칩니다.

Netscape의 SSL부터 최신 TLS 1.3까지. 대칭키/비대칭키 암호화의 조화, Handshake 과정 상세 분석(1.2 vs 1.3), CA 신뢰 사슬, 그리고 HTTPS의 동작 원리를 파헤칩니다.

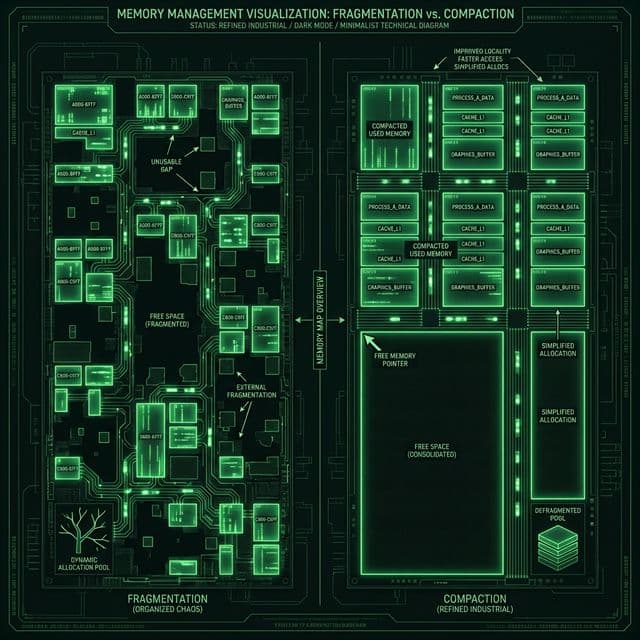

내 서버는 왜 걸핏하면 뻗을까? OS가 한정된 메모리를 쪼개 쓰는 처절한 사투. 단편화(Fragmentation)와의 전쟁.

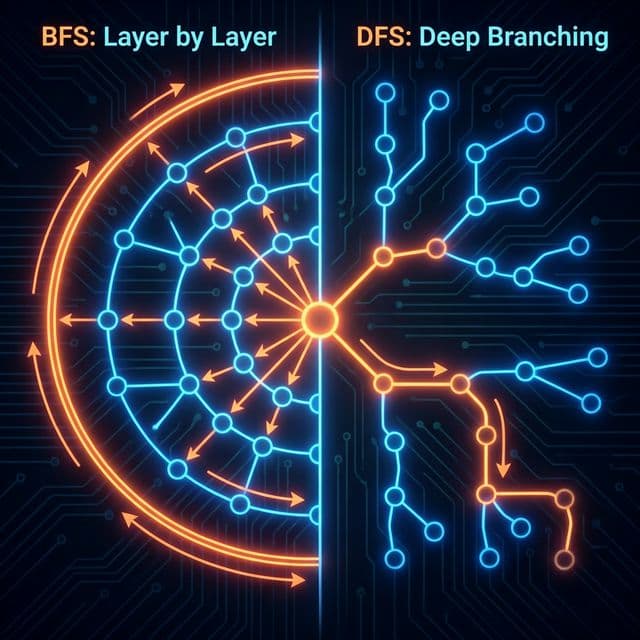

미로를 탈출하는 두 가지 방법. 넓게 퍼져나갈 것인가(BFS), 한 우물만 팔 것인가(DFS). 최단 경로는 누가 찾을까?

프론트엔드 개발자가 알아야 할 4가지 저장소의 차이점과 보안 이슈(XSS, CSRF), 그리고 언제 무엇을 써야 하는지에 대한 명확한 기준.

이름부터 빠릅니다. 피벗(Pivot)을 기준으로 나누고 또 나누는 분할 정복 알고리즘. 왜 최악엔 느린데도 가장 많이 쓰일까요?

내가 처음으로 만든 사이드 프로젝트를 배포했을 때, 크롬 주소창에 "안전하지 않음"이라는 회색 경고가 떴다. 당황했다. 내 서비스가 뭐가 안전하지 않다는 거지? 사용자가 들어와도 될지 말지 고민하는 게 느껴졌다. 그제야 깨달았다. HTTP로 운영하는 건 2025년에 용납되지 않는 일이라는 걸.

HTTPS를 붙여야 한다는 건 알았다. 그런데 "인증서"는 어디서 받는 거고, "CA"는 또 뭐고, 왜 "Self-Signed"는 안 된다는 건지 도통 이해가 안 갔다. 대칭키니 비대칭키니 하는 말들은 더욱 혼란스러웠다. "둘 다 암호화인데 뭐가 다르단 말이야?"

그래서 정리해본다. 내가 삽질했던 과정, 그리고 마침내 이해한 SSL/TLS의 동작 원리를. 결국 핵심은 이거였다. "편지를 안전하게 전달하려면, 먼저 편지를 암호화할 열쇠를 안전하게 보내야 한다."

처음 HTTPS를 공부하면서 가장 헷갈렸던 게 대칭키와 비대칭키의 차이였다. 둘 다 암호화를 한다는데, 왜 굳이 두 가지를 섞어 쓰는 거지?

같은 키 하나로 잠그고 푼다. 편지를 쓰는 사람과 읽는 사람이 같은 자물쇠 열쇠를 공유하는 것이다. AES 같은 알고리즘이 여기 속한다. 속도가 엄청 빠르다. CPU 부하가 적어서 대용량 데이터 전송에 적합하다.

하지만 치명적인 문제가 있다. "이 열쇠를 어떻게 안전하게 전달하지?" 인터넷은 기본적으로 도청당할 수 있는 네트워크다. 스타벅스 와이파이에서 평문으로 "우리 대칭키는 1234야!"라고 보내면 해커가 다 볼 수 있다. 그럼 의미가 없어진다.

공개키(Public Key)와 개인키(Private Key), 두 개의 키가 쌍을 이룬다. 공개키로 잠그면 개인키로만 열 수 있다. 마치 편지 봉투를 누구나 봉할 수 있지만(공개키), 뜯을 수 있는 건 주인만(개인키)인 것처럼.

RSA나 ECC 같은 알고리즘이 여기 속한다. 안전하다. 하지만 연산이 복잡해서 느리다. 대용량 데이터를 주고받기엔 너무 무겁다.

그래서 깨달은 게 이거다. "처음 만날 때만 비대칭키로 대칭키를 안전하게 교환하고, 그 뒤로는 빠른 대칭키로 통신하자!"

이 과정이 바로 TLS Handshake다. 마치 처음 만나는 사람과 악수할 때만 정중하게 하고, 친해지면 편하게 이야기하는 것처럼.

암호화만으로는 부족하다. 해커가 가짜 네이버 사이트를 만들고, 거기서 공개키를 주면서 "나 네이버야"라고 거짓말하면? 클라이언트는 그 공개키로 대칭키를 암호화해서 보낼 것이다. 해커는 그걸 풀어서 통신 내용을 다 볼 수 있다.

이게 바로 중간자 공격(Man-In-The-Middle, MITM)이다.

이 문제를 막는 게 인증서(Certificate)다. 인증서는 "제3자(CA)가 이 서버의 신원을 보증한다"는 보증서다.

인터넷 세상의 주민센터 같은 곳이다. DigiCert, Sectigo, Let's Encrypt 같은 기관들이 있다. 기업이나 개인이 CA에게 "내가 네이버를 운영한다"는 걸 증명하면(도메인 소유권 확인 등), CA가 인증서를 발급해준다.

인증서 안에는 이런 정보가 담긴다.

브라우저는 이렇게 확인한다.

이렇게 신뢰의 사슬(Chain of Trust)이 형성된다. 만약 해커가 만든 Self-Signed 인증서라면? 브라우저의 Trust Store에 그 CA가 없으니까, 빨간 경고창이 뜬다. "연결이 비공개로 설정되어 있지 않습니다."

개발할 때 로컬(localhost)에서 HTTPS를 테스트하고 싶었다. 그런데 Let's Encrypt는 공인 도메인만 지원한다. Self-Signed 인증서를 만들면 브라우저가 경고를 띄워서 불편하다.

그래서 찾은 게 mkcert였다.

# mkcert 설치 (macOS)

brew install mkcert

# 로컬 CA 생성 및 시스템 Trust Store에 등록

mkcert -install

# localhost용 인증서 생성

mkcert localhost 127.0.0.1 ::1

이렇게 하면 localhost.pem(인증서)와 localhost-key.pem(개인키) 파일이 생긴다. 이걸 개발 서버에 물려주면 된다.

// Node.js Express 예시

const https = require('https');

const fs = require('fs');

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

const options = {

key: fs.readFileSync('./localhost-key.pem'),

cert: fs.readFileSync('./localhost.pem')

};

https.createServer(options, app).listen(3000, () => {

console.log('HTTPS 서버 작동 중: https://localhost:3000');

});

브라우저에서 https://localhost:3000에 접속하면 경고 없이 자물쇠 아이콘이 뜬다. mkcert가 만든 로컬 CA가 시스템 Trust Store에 등록되어 있기 때문이다.

개발 중에 마주친 함정이 하나 더 있었다. HTTPS 페이지에서 HTTP 리소스를 불러오려고 하면 브라우저가 차단한다. 예를 들어 이런 코드.

<!-- 이건 막힌다 -->

<img src="http://example.com/image.jpg">

콘솔에 Mixed Content 에러가 뜬다. HTTPS 페이지는 "안전한 통신"을 보장하는데, 중간에 HTTP 리소스를 불러오면 해커가 거기에 악성 스크립트를 주입할 수 있기 때문이다.

해결법은 간단하다. 모든 리소스를 HTTPS로 불러오거나, 프로토콜 상대 URL(//example.com/image.jpg)을 쓰면 된다.

개발이 끝나고 실제로 배포할 때는 Let's Encrypt를 썼다. 무료고, 자동 갱신이 가능하다.

# Certbot 설치 (Ubuntu 기준)

sudo apt install certbot python3-certbot-nginx

# Nginx용 인증서 발급 및 자동 설정

sudo certbot --nginx -d mydomain.com -d www.mydomain.com

certbot이 알아서 도메인 소유권을 확인하고(ACME 챌린지), 인증서를 발급해서 Nginx 설정까지 해준다. 마법 같았다.

Nginx 설정 파일을 열어보니 이렇게 바뀌어 있었다.

server {

listen 443 ssl http2;

server_name mydomain.com;

ssl_certificate /etc/letsencrypt/live/mydomain.com/fullchain.pem;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/letsencrypt/live/mydomain.com/privkey.pem;

ssl_protocols TLSv1.2 TLSv1.3;

ssl_ciphers HIGH:!aNULL:!MD5;

# 나머지 설정...

}

그리고 자동 갱신도 설정해야 한다. Let's Encrypt 인증서는 90일마다 만료되기 때문이다.

# 크론 탭에 등록

sudo crontab -e

# 매일 새벽 2시에 갱신 시도

0 2 * * * certbot renew --quiet

이제 걱정 없다. 인증서가 알아서 갱신된다.

처음엔 그냥 "HTTPS를 켜면 되는구나"라고만 생각했는데, 깊게 파보니 TLS 버전에 따라 속도 차이가 크다는 걸 알게 됐다.

클라이언트와 서버가 키를 교환하기 위해 두 번 왕복(2 Round Trip)해야 한다.

여기까지 두 번 왕복해야 한다. 지연 시간(Latency)이 높은 모바일 네트워크에서는 꽤 느리다.

TLS 1.3는 과정을 대폭 줄였다.

이렇게 한 번 왕복만 하면 데이터 전송이 시작된다. 속도가 거의 2배 빨라진다.

실제로 Wireshark로 패킷을 찍어보니 TLS 1.3이 확실히 빨랐다. 특히 모바일 환경에서 체감이 컸다.

예전에는 서버의 개인키 하나로 모든 세션 키를 복호화할 수 있었다. 만약 해커가 5년 전의 암호화된 패킷을 몽땅 녹화해뒀다가, 나중에 서버를 해킹해서 개인키를 훔치면? 과거의 모든 통신이 다 복호화된다. 소름 끼치는 일이다.

PFS는 이걸 막는다. 매 세션마다 임시 키(Ephemeral Key)를 생성하고, 세션이 끝나면 그 키를 버린다. 서버 개인키가 털려도, 과거 세션 키는 복구할 수 없다. 왜냐하면 그 키는 서버에 저장된 적도 없고, 전송된 적도 없기 때문이다. (Diffie-Hellman 키 교환 방식 덕분)

사용자가 실수로 http://mysite.com이라고 입력하면, 해커가 중간에서 SSL Stripping 공격을 할 수 있다. 즉, 사용자는 평생 HTTPS로 접속하지 못하고 HTTP로만 통신하게 된다.

HSTS 헤더를 보내면 브라우저에게 이렇게 명령한다. "앞으로 1년간 이 사이트는 무조건 HTTPS로만 접속해. 사용자가 http://를 입력해도 너가 알아서 https://로 바꿔."

add_header Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains" always;

이제 한 번 HTTPS로 접속한 사용자는, 다음부터 브라우저가 자동으로 HTTPS로 요청을 보낸다. 해커가 중간에 끼어들 틈이 없다.

인증서가 만료 전에 도난당하거나 폐기(Revoke)될 수 있다. 브라우저는 이걸 어떻게 확인할까?

OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol): 브라우저가 CA에게 "이 인증서 아직 유효해?"라고 물어본다. 문제는 느리고, 프라이버시가 새나간다. (CA가 사용자가 어느 사이트에 접속하는지 다 안다)

OCSP Stapling: 서버가 주기적으로 CA에게 물어보고, "이 인증서 유효함"이라는 서명된 타임스탬프를 받아둔다. 클라이언트에게 인증서를 줄 때 그 증명도 함께 보낸다. 브라우저는 CA에 직접 물어볼 필요가 없다. 빠르고 프라이버시도 보호된다.

터미널에서 openssl 도구로 네이버의 인증서를 까볼 수 있다.

openssl s_client -connect www.naver.com:443 -showcerts

출력 결과를 보면 이런 정보가 나온다.

Certificate chain

0 s:CN = www.naver.com

i:CN = DigiCert TLS RSA SHA256 2020 CA1

1 s:CN = DigiCert TLS RSA SHA256 2020 CA1

i:CN = DigiCert Global Root CA

이 0 → 1 → 2의 연결 고리가 Chain of Trust다. 브라우저는 2번(루트)이 자기 Trust Store에 있으니 신뢰하고, 2번이 1번을 보증하고, 1번이 0번을 보증하니까, 최종적으로 0번(네이버)을 믿는다.

A: 거의 아니다. CPU에 AES-NI(암호화 가속 명령어)가 내장되어 있어서, 암호화 오버헤드는 무시할 수준이다. 오히려 HTTP/2는 HTTPS 위에서만 동작하고, 멀티플렉싱으로 훨씬 빠르다. 결론: HTTPS가 더 빠르다.

A: 전혀 아니다. 암호화 강도(AES-256, RSA-2048 등)는 유료 인증서와 똑같다. 유료 인증서는 기업 실존 확인(EV/OV) 같은 보험 서비스를 추가로 제공할 뿐이다. 기술적 보안은 동일하다.

A: 해커도 "내가 네이버다"라고 주장하는 Self-Signed 인증서를 만들 수 있기 때문이다. CA의 보증이 없으면 신뢰할 수 없다. 단, 내부망이나 로컬 개발 환경에서는 쓴다. (mkcert 같은 도구로)

A: 암호화/복호화 연산을 웹 서버 대신 로드 밸런서가 전담하는 것이다. 웹 서버는 평문만 처리하니까 부하가 줄어든다. 단, 로드 밸런서와 웹 서버 사이 구간은 평문이므로, 내부 네트워크가 안전해야 한다.

HTTPS는 단순히 "자물쇠 아이콘"을 띄우기 위한 게 아니다. 사용자의 신뢰를 얻는 기본 전제 조건이다.

처음 배포할 때 "안전하지 않음" 경고를 봤던 그 날, 지금 생각하면 좋은 경험이었다. 덕분에 HTTPS의 내부를 깊게 이해할 수 있었다. 이제는 certbot 한 줄로 해결하지만, 그 안에서 무슨 일이 일어나는지 안다는 게 큰 차이다.

아직도 관습적으로 "SSL 인증서"라고 부르지만, 기술적으로는 모두 TLS다. SSL 프로토콜 자체는 POODLE 같은 취약점 때문에 퇴출됐다.

I'll never forget deploying my first side project. Everything worked fine in localhost, but when I pushed it live, Chrome greeted me with a gray "Not Secure" label in the address bar. My heart sank. Would users even trust this site enough to use it?

That's when I realized: running HTTP in 2025 is basically digital malpractice.

I knew I needed HTTPS, but the terminology was overwhelming. What's a Certificate Authority? Why can't I just use a self-signed certificate? And what's the difference between symmetric and asymmetric encryption anyway? They both encrypt stuff, right?

So I dove in, made mistakes, and eventually figured it out. The aha moment came when I realized: securing communication is like sending a locked box—you first need to safely send the key.

The biggest mental hurdle was understanding why we need two types of encryption. Why can't we just pick one and stick with it?

Imagine you and I share the same house key. You lock a door with it, I unlock it with the same key. That's symmetric encryption (like AES). It's blazing fast because the math is simple. Perfect for encrypting large amounts of data.

But here's the catch: how do we safely share that key in the first place? If we're communicating over the internet (which anyone can eavesdrop on), sending "Hey, our key is 1234!" in plain text is game over. A hacker on the same Wi-Fi network can intercept it, and suddenly they can decrypt everything.

This uses a pair of keys: a public key (which anyone can have) and a private key (which only you keep). It's like a mailbox: anyone can drop a letter in (encrypt with the public key), but only the owner can open it (decrypt with the private key).

RSA and ECC are asymmetric algorithms. They're incredibly secure, but also computationally expensive. Using them to encrypt a video file would take forever.

The breakthrough insight: use asymmetric encryption only during the initial handshake to safely exchange a symmetric key, then switch to symmetric encryption for actual data transfer.

Here's the flow:

This dance is called the TLS Handshake. It's like shaking hands formally when you first meet someone, then relaxing once you're friends.

Encryption alone isn't enough. What if a hacker creates a fake Naver site, hands you a public key, and says "I'm Naver, trust me"? You'd encrypt your session key with that public key and send it over. The hacker would decrypt it and read everything.

This is called a Man-In-The-Middle (MITM) attack.

The solution? Certificates signed by trusted third parties.

Think of a CA as the DMV of the internet. Organizations like DigiCert, Sectigo, and Let's Encrypt verify your identity (usually by confirming you own a domain), then issue you a certificate.

That certificate contains:

When you visit a website:

This is the Chain of Trust. If a hacker uses a self-signed certificate (one they signed themselves), the browser won't find that CA in its Trust Store and will show a scary red warning: "Your connection is not private."

When developing locally, I wanted to test HTTPS. But Let's Encrypt only works with public domains. If I used a self-signed certificate, the browser kept throwing warnings.

That's when I found mkcert.

# Install mkcert (macOS)

brew install mkcert

# Create a local CA and add it to the system Trust Store

mkcert -install

# Generate a certificate for localhost

mkcert localhost 127.0.0.1 ::1

This creates localhost.pem (certificate) and localhost-key.pem (private key). Plug them into your dev server:

// Node.js Express example

const https = require('https');

const fs = require('fs');

const express = require('express');

const app = express();

const options = {

key: fs.readFileSync('./localhost-key.pem'),

cert: fs.readFileSync('./localhost.pem')

};

https.createServer(options, app).listen(3000, () => {

console.log('HTTPS server running at https://localhost:3000');

});

Now https://localhost:3000 works without warnings, because mkcert added its local CA to your system's Trust Store.

I ran into another issue: if you load an HTTPS page but try to fetch HTTP resources, the browser blocks them.

<!-- This will be blocked -->

<img src="http://example.com/image.jpg">

The console will scream Mixed Content Error. Why? Because an attacker could inject malicious scripts into that HTTP resource, breaking the security guarantee of HTTPS.

The fix: load all resources via HTTPS, or use protocol-relative URLs (//example.com/image.jpg).

For production, I used Let's Encrypt. It's free, automated, and trusted by all browsers.

# Install Certbot (Ubuntu)

sudo apt install certbot python3-certbot-nginx

# Get a certificate and auto-configure Nginx

sudo certbot --nginx -d mydomain.com -d www.mydomain.com

Certbot verifies domain ownership via the ACME protocol, issues a certificate, and even updates your Nginx config automatically. It felt like magic.

Here's what the Nginx config looked like after:

server {

listen 443 ssl http2;

server_name mydomain.com;

ssl_certificate /etc/letsencrypt/live/mydomain.com/fullchain.pem;

ssl_certificate_key /etc/letsencrypt/live/mydomain.com/privkey.pem;

ssl_protocols TLSv1.2 TLSv1.3;

ssl_ciphers HIGH:!aNULL:!MD5;

# Other settings...

}

Let's Encrypt certificates expire every 90 days, so I set up auto-renewal:

# Add to crontab

sudo crontab -e

# Auto-renew at 2 AM daily

0 2 * * * certbot renew --quiet

No more worrying about expiration.

Once I got HTTPS working, I got curious: does the TLS version matter? Turns out, it matters a lot for speed.

The client and server have to exchange messages twice (2 round trips) before data transfer begins.

On high-latency connections (like mobile networks), this delay is noticeable.

TLS 1.3 slashes the process dramatically.

Only one round trip. Speed nearly doubles. I verified this by capturing packets with Wireshark—the difference was stark, especially on mobile.

In older SSL implementations, if a hacker recorded all your encrypted traffic and later stole the server's private key, they could decrypt everything retroactively. Scary.

PFS fixes this by generating a unique session key for every session using ephemeral keys (like Diffie-Hellman). These keys are never stored or transmitted, so even if the server's private key is compromised later, past sessions remain secure. The session keys are mathematically impossible to recover.

Hackers can perform SSL stripping attacks: if a user types http://mysite.com, the attacker intercepts it and keeps the connection on HTTP, so the user never sees HTTPS.

HSTS prevents this by telling the browser: "For the next year, only connect to me via HTTPS. If the user types http://, upgrade it to https:// automatically."

add_header Strict-Transport-Security "max-age=31536000; includeSubDomains" always;

Once a user visits your site via HTTPS, their browser remembers and always uses HTTPS from then on—no chance for an attacker to downgrade it.

What if a certificate is stolen or compromised before it expires? The CA can revoke it, but how does the browser check?

OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol): The browser asks the CA, "Is this cert still good?" This is slow and leaks privacy (the CA knows which sites you visit).

OCSP Stapling: The server periodically asks the CA and gets a signed "This cert is valid" timestamp. When a client connects, the server attaches this proof to the certificate. The browser doesn't need to contact the CA at all. Faster and more private.

You can inspect any site's certificate using OpenSSL:

openssl s_client -connect www.naver.com:443 -showcerts

Output breakdown:

Certificate chain

0 s:CN = www.naver.com

i:CN = DigiCert TLS RSA SHA256 2020 CA1

1 s:CN = DigiCert TLS RSA SHA256 2020 CA1

i:CN = DigiCert Global Root CA

This 0 → 1 → 2 chain is the Chain of Trust. The browser trusts #2 (Root CA), which vouches for #1 (Intermediate), which vouches for #0 (Naver).

A: Barely. Modern CPUs have AES-NI (hardware acceleration for encryption), so overhead is negligible. Plus, HTTP/2 (which requires HTTPS) is much faster than HTTP/1.1 due to multiplexing. In practice, HTTPS is often faster.

A: No. The encryption strength (AES-256, RSA-2048, etc.) is identical. Paid certificates mainly offer Extended Validation (EV) or insurance against mis-issuance. The technical security is the same.

A: Because anyone (including hackers) can create one and claim to be Google. Without CA verification, there's no trust. However, self-signed certs are fine for internal networks or dev environments (using tools like mkcert).

A: It means moving encryption/decryption work from the web server to a load balancer. The web server only handles plaintext, reducing its CPU load. However, the connection between the load balancer and web server is unencrypted, so your internal network must be secure.

HTTPS isn't just about getting a green padlock in the browser. It's about earning user trust—the baseline for any modern web service.

That first "Not Secure" warning I saw? It was a gift. It forced me to understand how the internet actually stays safe. Now, even though I can set up HTTPS with a single certbot command, I know exactly what's happening under the hood—and that makes all the difference.

We still say "SSL certificate" out of habit, but technically it's all TLS now. The SSL protocol itself was deprecated due to vulnerabilities like POODLE.