Trie(트라이): 검색어 자동완성은 어떻게 0.01초 만에 나올까?

문자열 검색에 특화된 트리 자료구조. 접두사 트리(Prefix Tree)라고도 불리는 Trie의 구조와 삽입/검색 과정, 그리고 메모리 효율을 극대화한 Radix Tree까지 다뤄봤습니다.

문자열 검색에 특화된 트리 자료구조. 접두사 트리(Prefix Tree)라고도 불리는 Trie의 구조와 삽입/검색 과정, 그리고 메모리 효율을 극대화한 Radix Tree까지 다뤄봤습니다.

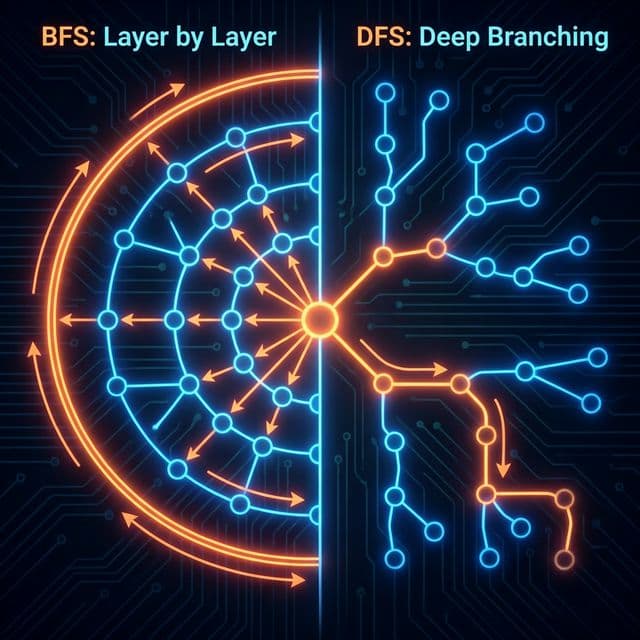

미로를 탈출하는 두 가지 방법. 넓게 퍼져나갈 것인가(BFS), 한 우물만 팔 것인가(DFS). 최단 경로는 누가 찾을까?

이름부터 빠릅니다. 피벗(Pivot)을 기준으로 나누고 또 나누는 분할 정복 알고리즘. 왜 최악엔 느린데도 가장 많이 쓰일까요?

업다운 게임으로 배우는 이진 탐색 트리. 왜 데이터베이스는 해시 테이블 대신 B-Tree를 쓸까? AVL 트리, 레드블랙 트리, 그리고 Splay Tree까지.

CPU는 하나인데 프로그램은 수십 개 실행됩니다. 운영체제가 0.01초 단위로 프로세스를 교체하며 '동시 실행'의 환상을 만드는 마술. 선점형 vs 비선점형, 기아 현상(Starvation), 그리고 현대적 해법인 MLFQ를 파헤칩니다.

스타트업에서 검색 기능을 만들어야 했다. 사용자가 검색창에 타이핑하는 순간마다 자동완성 추천어를 띄워주는 그 기능 말이다. 처음엔 단순하게 생각했다. "DB에 있는 단어들 전부 가져와서 startsWith()로 필터링하면 되겠지?" 그런데 막상 구현해보니 사용자가 키를 하나씩 누를 때마다 수천 개의 단어를 전부 순회하면서 앞글자를 비교했다. 단어가 10만 개만 넘어가도 체감할 수 있을 만큼 느려졌다.

// 초기 구현 - O(N × M) 시간 복잡도

function autocomplete(prefix, words) {

return words.filter(word => word.startsWith(prefix));

}

이건 말이 안 된다고 생각했다. 구글은 수십억 개의 검색어 중에서도 찰나의 순간에 추천어를 보여주는데, 내가 만든 건 고작 10만 개로도 버벅인다니. 데이터 개수($N$)에 영향받지 않는 검색 방법이 필요했다. 그때 알게 된 게 Trie(트라이)였다.

처음엔 "트리(Tree)의 오타 아닌가?" 싶었다. 발음도 "트리"처럼 읽는 사람도 있고 "트라이"라고 읽는 사람도 있어서 혼란스러웠다. 나중에 알고 보니 Retrieval(검색)에서 가운데 부분을 따온 이름이었다. 발음은 원래 "트리"와 구분하기 위해 "트라이"로 읽는 게 표준이라고 한다. 이름부터 검색에 특화되어 있다는 걸 암시하는 자료구조였다.

Trie를 처음 봤을 때 가장 혼란스러웠던 부분은 일반적인 이진 탐색 트리(BST)와 전혀 다르게 생겼다는 점이었다. BST는 노드 하나에 값이 있고, 왼쪽/오른쪽 자식이 있다. 그런데 Trie는 노드 자체에 '문자'를 저장하는 게 아니라, 간선(Edge)에 문자를 저장하는 것처럼 동작한다. 정확히는 부모에서 자식으로 가는 경로에 문자가 매핑되어 있다.

더 혼란스러웠던 건 각 노드가 자식을 26개(알파벳 개수)나 가질 수 있다는 점이었다. "이게 트리 맞나? 그래프 아닌가?" 싶었다. 결국 받아들였던 건, Trie는 문자열의 각 글자를 경로로 표현하는 트리라는 것이다.

루트 노드는 비어있고, 거기서부터 C로 가는 경로가 있으면 C에 해당하는 자식 노드로 이동한다. 그 다음 A로 가는 경로가 있으면 또 이동한다. 마지막 글자에 도달하면 "여기가 단어의 끝이다"라는 표시(isEndOfWord)를 해둔다. 이 표시가 없으면 그냥 다른 단어의 접두사일 뿐이다. 예를 들어 "CAR"와 "CARD"가 저장되어 있다면, C-A-R 경로까지는 공유하지만 R 노드에 isEndOfWord = True가 있어야 "CAR"도 단어로 인식된다.

처음엔 이 구조가 비효율적으로 느껴졌다. "그냥 해시맵에 단어 전체를 키로 넣으면 $O(1)$로 검색되는데, 왜 이렇게 복잡하게?" 그런데 곰곰이 생각해보니 해시맵은 정확히 일치하는 단어만 찾을 수 있다. "app"으로 시작하는 모든 단어를 찾으려면 해시맵의 모든 키를 순회해야 한다. 결국 $O(N)$이다. Trie는 이 접두사 검색(Prefix Search)을 단어 길이에만 비례하는 시간($O(L)$)으로 해결한다는 게 핵심이었다.

BST는 노드의 값을 비교해서 왼쪽/오른쪽을 결정한다. Trie는 비교가 필요 없다. 문자 C를 찾으려면 현재 노드의 children['C']를 보면 된다. 있으면 가고, 없으면 끝이다. 경로를 따라가는 것 자체가 검색이다.

이 깨달음이 와닿았던 순간은 직접 손으로 "CAR", "CAT", "CARD", "DO"를 Trie에 넣어보면서였다.

Root

└─ C

└─ A

└─ R [끝]

Root

└─ C

└─ A

├─ R [끝]

└─ T [끝]

C와 A는 이미 있으니 재사용하고, A에서 새로운 자식 T를 추가했다. 메모리를 절약하는 원리가 이해됐다.

Root

└─ C

└─ A

├─ R [끝]

│ └─ D [끝]

└─ T [끝]

C-A-R까지는 이미 있고, R에서 D를 추가한다. R 노드의 isEndOfWord는 그대로 True이므로 "CAR"와 "CARD" 둘 다 유효한 단어로 남는다.

Root

├─ C

│ └─ A

│ ├─ R [끝]

│ │ └─ D [끝]

│ └─ T [끝]

└─ D

└─ O [끝]

루트에서 새로운 경로 D-O가 생겼다. 전혀 다른 접두사이므로 공유되지 않는다.

이 과정을 보고 나니 Trie가 공통 접두사를 최대한 공유하는 구조라는 게 명확히 정리됐다. "CAT"과 "CAR"은 "CA"까지 같으므로 그 부분만 한 번 저장하고, 이후부터 분기한다. 이게 메모리 효율성의 핵심이다(물론 나중에 설명하겠지만, 역설적으로 메모리 낭비도 심하다).

Trie의 노드는 보통 두 가지 요소로 구성된다.

children: 다음 문자로 가는 포인터들의 집합

Node* children[26] (알파벳 소문자만 다룬다면)unordered_map<char, Node*> children (메모리 절약, 약간 느림)isEndOfWord: 이 노드에서 끝나는 단어가 있는지 표시하는 플래그

어떤 구현은 여기에 단어 빈도수(frequency), 사용자 클릭 수(weight) 등을 추가로 저장해서 자동완성 순위를 매기기도 한다.

Insert(word):

1. current = root

2. for each char in word:

if char not in current.children:

current.children[char] = new TrieNode()

current = current.children[char]

3. current.isEndOfWord = True

시간 복잡도: $O(L)$ (L은 단어 길이)

공간 복잡도: 최악 $O(L)$ (모든 글자가 신규 노드를 만들 때)

Search(word):

1. current = root

2. for each char in word:

if char not in current.children:

return False

current = current.children[char]

3. return current.isEndOfWord

시간 복잡도: $O(L)$

여기서 중요한 점은 3번째 단계다. 경로를 끝까지 따라갔더라도 isEndOfWord가 False면 그 단어는 저장되지 않은 것이다. 예를 들어 "CARD"만 넣고 "CAR"은 안 넣었다면, "CAR"을 검색할 때 C-A-R까지는 도달할 수 있지만 R 노드의 isEndOfWord가 False이므로 존재하지 않는다고 판단한다.

StartsWith(prefix):

1. current = root

2. for each char in prefix:

if char not in current.children:

return False

current = current.children[char]

3. return True # 끝까지 도달하기만 하면 OK

시간 복잡도: $O(L)$

Search와 거의 같지만, isEndOfWord 체크를 안 한다. 접두사까지만 일치하면 된다. 이 연산을 확장해서 "이 접두사로 시작하는 모든 단어 찾기"를 구현할 수 있다. 접두사 노드까지 이동한 후, 거기서부터 DFS/BFS로 isEndOfWord == True인 모든 노드를 찾으면 된다.

삭제는 조금 까다롭다. 단순히 isEndOfWord만 False로 바꾸면 되는 경우도 있지만, 그 노드가 다른 단어의 중간 경로가 아니라면 메모리 누수를 막기 위해 노드 자체를 삭제해야 한다.

Delete(word):

1. 재귀적으로 경로를 따라가면서 삭제 플래그를 세운다

2. 되돌아오면서(backtrack) 각 노드를 검사:

- 자식이 없고 끝단어도 아니면 → 부모에서 연결 끊고 삭제

- 자식이 있거나 다른 단어의 끝이면 → 유지

시간 복잡도: $O(L)$

실제 구현에서는 재귀를 사용하거나, 역추적용 스택을 만들어서 처리한다. 삭제는 실제로 자주 쓰이진 않지만(검색 로그는 보통 삭제 안 함), 동적으로 사전을 관리하는 시스템에서는 필수다.

| 연산 | Trie | HashMap | Binary Search Tree |

|---|---|---|---|

| 정확 검색 | $O(L)$ | $O(L)$ (해시 계산) | $O(L \log N)$ (문자열 비교 포함) |

| 접두사 검색 | $O(L)$ | $O(N \cdot L)$ (전체 순회) | $O(L \log N + K)$ (K는 결과 개수) |

| 삽입 | $O(L)$ | $O(L)$ | $O(L \log N)$ |

| 공간 복잡도 | $O(ALPHABET \cdot N \cdot L)$ | $O(N \cdot L)$ | $O(N \cdot L)$ |

예를 들어 영어 소문자 26개를 배열로 관리하면 노드 하나당 26개의 포인터(보통 64비트 시스템에서 각각 8바이트 = 208바이트)가 필요하다. "HELLO" 하나 저장하려고 5개 노드 × 208바이트 = 1KB 이상을 쓴다. 실제로는 대부분이 null 포인터다.

Trie를 실제에 적용하려다가 제일 먼저 부딪히는 문제가 메모리 낭비다. 이론적으로는 공통 접두사를 공유해서 효율적일 것 같지만, 실제로는 각 노드가 가능한 모든 다음 문자를 위한 포인터 공간을 미리 확보해야 한다.

알파벳 소문자만 사용하는 영어 단어 사전을 만든다고 가정:

Node* children[26] + bool isEndOfWord = 26 × 8바이트 + 1바이트 ≈ 209바이트한글을 다루면 더 심각하다. 초성 19개 × 중성 21개 × 종성 28개 = 11,172개의 조합이 가능하므로, 배열로 관리하면 노드 하나가 수십 KB를 차지한다. 이 경우 해시맵을 쓰는 게 필수다.

# 배열 방식 - 빠르지만 메모리 낭비

class TrieNodeArray:

def __init__(self):

self.children = [None] * 26 # 26개 포인터 공간

self.is_end = False

# 해시맵 방식 - 느리지만 실제 사용만 저장

class TrieNodeDict:

def __init__(self):

self.children = {} # 동적으로 필요할 때만 추가

self.is_end = False

프로덕션에서는 대부분 해시맵 방식을 쓴다. 배열의 속도 이점($O(1)$ vs 해시맵의 평균 $O(1)$, 최악 $O(k)$, k는 키 길이)은 미미하지만, 메모리 차이는 수십 배에 달한다.

메모리 낭비를 줄이기 위한 가장 유명한 최적화가 Radix Tree다. 다른 이름으로 Patricia Trie(Practical Algorithm To Retrieve Information Coded In Alphanumeric)라고도 한다.

일반 Trie에서는 "ROMANTIC"을 저장하면:

R -> O -> M -> A -> N -> T -> I -> C [끝]

8개의 노드가 필요하다. 각 노드가 209바이트면 약 1.6KB다.

Radix Tree에서는:

ROMANTIC [끝]

하나의 노드에 문자열 전체를 저장한다. 만약 나중에 "ROME"이 추가되면:

ROM

├─ ANTIC [끝]

└─ E [끝]

공통 부분 "ROM"까지는 하나의 노드에 저장하고, 거기서 분기한다. 이렇게 하면 노드 개수가 대폭 줄어든다.

/api/users/profile/settings/privacy 같은 경로는 중간에 분기가 거의 없음실제 사례:

이론은 이해했으니, 실제로 동작하는 자동완성을 만들어보자.

class TrieNode:

def __init__(self):

self.children = {} # 해시맵으로 메모리 절약

self.is_end_of_word = False

self.word = None # 자동완성용: 완성된 단어 저장

class Trie:

def __init__(self):

self.root = TrieNode()

def insert(self, word):

"""단어 삽입 - O(L)"""

node = self.root

for char in word:

if char not in node.children:

node.children[char] = TrieNode()

node = node.children[char]

node.is_end_of_word = True

node.word = word # 나중에 수집할 때 편리

def search(self, word):

"""정확한 단어 검색 - O(L)"""

node = self.root

for char in word:

if char not in node.children:

return False

node = node.children[char]

return node.is_end_of_word

def starts_with(self, prefix):

"""접두사 존재 여부 - O(L)"""

node = self.root

for char in prefix:

if char not in node.children:

return False

node = node.children[char]

return True

def autocomplete(self, prefix, limit=10):

"""

접두사로 시작하는 단어 최대 limit개 반환

시간 복잡도: O(L + K × M)

- L: 접두사 길이 (접두사 노드까지 이동)

- K: 결과 개수

- M: 평균 단어 길이 (DFS 탐색)

"""

node = self.root

# 1단계: 접두사 끝까지 이동

for char in prefix:

if char not in node.children:

return [] # 접두사 자체가 없음

node = node.children[char]

# 2단계: 그 노드부터 DFS로 모든 단어 수집

results = []

self._dfs_collect(node, results, limit)

return results

def _dfs_collect(self, node, results, limit):

"""DFS로 끝단어 노드 찾기"""

if len(results) >= limit:

return # 충분히 모았으면 조기 종료

if node.is_end_of_word:

results.append(node.word)

# 자식들을 알파벳 순서로 탐색 (정렬된 결과)

for char in sorted(node.children.keys()):

self._dfs_collect(node.children[char], results, limit)

def delete(self, word):

"""

단어 삭제 - O(L)

빈 노드는 역추적하면서 정리

"""

def _delete_recursive(node, word, index):

if index == len(word):

# 끝에 도달 - 단어 표시 제거

if not node.is_end_of_word:

return False # 애초에 없던 단어

node.is_end_of_word = False

node.word = None

# 자식이 없으면 이 노드 삭제 가능

return len(node.children) == 0

char = word[index]

if char not in node.children:

return False # 경로가 없음

child = node.children[char]

should_delete_child = _delete_recursive(child, word, index + 1)

if should_delete_child:

# 자식 노드를 삭제해야 함

del node.children[char]

# 현재 노드도 삭제 가능한지 확인

return len(node.children) == 0 and not node.is_end_of_word

return False

_delete_recursive(self.root, word, 0)

# 사전 구축

trie = Trie()

words = ["apple", "app", "application", "apply", "apricot",

"banana", "band", "bandana", "can", "cat", "car"]

for word in words:

trie.insert(word)

# 자동완성 테스트

print(trie.autocomplete("app"))

# 출력: ['app', 'apple', 'application', 'apply']

print(trie.autocomplete("ban"))

# 출력: ['banana', 'band', 'bandana']

print(trie.autocomplete("ca"))

# 출력: ['can', 'car', 'cat']

# 정확 검색

print(trie.search("app")) # True

print(trie.search("appl")) # False (끝표시 없음)

print(trie.search("application")) # True

# 삭제 후 재검색

trie.delete("app")

print(trie.search("app")) # False

print(trie.autocomplete("app")) # ['apple', 'application', 'apply']

# "app"은 사라졌지만 경로는 남아있어서 다른 단어들은 유지됨

라우터는 IP 주소의 네트워크 부분을 보고 다음 홉(hop)을 결정한다. 예를 들어:

192.168.1.0/24 → Gateway A192.168.0.0/16 → Gateway B0.0.0.0/0 (default) → Gateway CIP 192.168.1.50이 들어오면 가장 긴 일치 접두사인 /24를 찾아야 한다. 이를 Longest Prefix Match라고 하는데, Trie(특히 Radix Tree)로 구현하면 효율적이다.

Binary Trie for IP routing:

Root

└─ 1 (first bit of 192 = 11000000)

└─ 1

└─ 0

... (32bit depth)

실제로는 비트 단위가 아닌 8비트(옥텟) 단위로 압축해서 Radix Tree를 만든다.

옛날 피처폰의 T9(Text on 9 keys) 입력 방식도 Trie를 활용했다.

사용자가 4663을 누르면 GOOD, HOME, GONE 등 여러 단어가 가능하다. Trie에 각 단어를 숫자 시퀀스로 변환해서 저장하고, 빈도수가 높은 순으로 추천했다.

오타를 교정하려면 입력된 단어와 "비슷한" 단어를 찾아야 한다. Trie를 순회하면서 편집 거리(Levenshtein Distance)가 1~2 이내인 단어를 찾는다.

def fuzzy_search(trie_node, word, max_distance):

"""

편집 거리가 max_distance 이내인 단어 찾기

동적 프로그래밍 + Trie 순회

"""

# DP 배열로 편집 거리 계산하면서 Trie 탐색

# 구현 복잡도 높음 - 라이브러리 사용 권장 (SymSpell, BK-tree 등)

Trie와 BST의 중간 형태다. 각 노드가 3개의 자식(왼쪽, 중간, 오른쪽)을 가진다.

메모리는 Trie보다 적게 쓰지만, 검색 속도는 $O(L \log \Sigma)$로 약간 느리다. 실제로는 잘 안 쓰지만, 임베디드 환경에서 고려 대상이다.

일본어 형태소 분석기 MeCab, Kuromoji 등에서 사용하는 기법이다. 두 개의 배열(BASE, CHECK)로 Trie를 표현해서 메모리를 극도로 절약한다. 구현이 매우 복잡하지만, 읽기 전용 대용량 사전에서는 최고 성능을 낸다.

Trie를 프로덕션에 도입하기 전에 확인할 것들:

| 기술 | 장점 | 단점 | 사용 사례 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trie (In-memory) | 빠른 접두사 검색 | 메모리 多 | 소규모 자동완성 |

| Elasticsearch | 분산, 전문 검색 | 운영 복잡도 | 대규모 검색 엔진 |

| Redis Sorted Set | 간단, 스코어링 | 접두사 검색 비효율 | 랭킹 기반 추천 |

| PostgreSQL LIKE | 별도 구축 불필요 | 느림 (인덱스 미사용 시) | 소규모 DB 검색 |

| SQLite FTS5 | 경량, 임베디드 | 고급 기능 부족 | 모바일 앱 검색 |

결국 받아들인 건, Trie는 접두사 검색이라는 특정 문제에 최적화된 전문 도구라는 점이다. 만능은 아니다. 하지만 자동완성, 사전 검색, IP 라우팅처럼 "앞부분이 일치하는 것을 빠르게 찾아야 하는" 상황에서는 대체 불가능한 성능을 낸다.

메모리 문제는 해시맵 기반 노드, Radix Tree, 외부 저장소 등으로 완화할 수 있다. 중요한 건 문제의 특성을 정확히 파악하고, Trie의 강점과 약점을 이해한 상태에서 선택하는 것이다.

구글 검색창에 타이핑할 때마다 나타나는 그 추천어들. 이제는 그 뒤에서 Trie가 $O(L)$ 시간에 수백만 개의 단어를 뒤지고 있다는 걸 안다. 그게 와닿았던 순간, Trie는 단순한 자료구조가 아니라 실시간 사용자 경험을 만드는 기술로 다가왔다.

해시 테이블은 정확히 일치하는 키만 찾을 수 있다. "app"으로 시작하는 모든 단어를 찾으려면 전체 키를 순회해야 하므로 $O(N)$이다. Trie는 접두사 검색이 $O(L)$로 가능하다. 또한 해시 충돌 공격에 취약하지만, Trie는 결정론적 성능을 보장한다.

Q2. Trie와 Suffix Tree의 차이는 무엇인가요?Trie는 단어의 시작 부분(접두사)을 공유한다. Suffix Tree는 문자열의 모든 접미사를 저장해서 문자열 내 패턴 매칭에 사용한다. 예를 들어 "BANANA"의 Suffix Tree는 "BANANA", "ANANA", "NANA", "ANA", "NA", "A"를 모두 저장한다. 용도가 완전히 다르다.

Q3. 한글이나 이모지는 어떻게 처리하나요?대부분은 검색 엔진(Elasticsearch, Solr)이나 Redis의 Sorted Set, PostgreSQL의 Full-Text Search를 활용한다. 하지만 네트워크 장비(라우터), 임베디드 시스템, 게임 엔진의 명령어 파서 등에서는 직접 구현한 최적화된 Trie를 쓴다. 특히 메모리와 레이턴시가 중요한 환경에서는 Double Array Trie 같은 고급 기법을 사용한다.

Q5. Trie 노드를 배열로 만들지 해시맵으로 만들지 어떻게 결정하나요?I was building a search feature for a startup. Users type in a search box, and we show autocomplete suggestions in real-time. My first attempt was embarrassingly simple: "Just fetch all words from the database and filter with startsWith(), right?" It worked on my laptop with a few hundred test words. But when we loaded 100,000 real product names, every keystroke triggered a full scan through all entries. The delay was noticeable, and users complained.

I looked at how Google handles billions of search queries and still suggests completions in milliseconds. There had to be a data structure where lookup time depends only on the word length, not the dictionary size. That's when I discovered the Trie (pronounced "try", derived from re-trie-val). The name itself hints at its purpose: retrieval operations.

At first, I thought it was just a typo of "Tree." Even the pronunciation was confusing—some people say "tree," others say "try." Later, I learned the official pronunciation is "try" to distinguish it from binary trees. The structure was specifically designed for string searches, and its name tells the story.

When I first saw a Trie diagram, I was confused. Binary Search Trees (BST) store values in nodes and have left/right children. Tries don't store characters in nodes themselves—instead, edges (or the path from parent to child) represent characters. Or more accurately, each node has a mapping of characters to child nodes.

What threw me off was that each node could have 26 children (for lowercase English letters). "Is this even a tree? Looks more like a graph," I thought. Eventually, I accepted that a Trie is a tree where each character in a string corresponds to a path from the root.

The root node is empty. From there, if you have a path labeled C, you move to the C child node. Then if there's a path labeled A, you move to the A child. When you reach the last character, you mark that node as "end of word" (isEndOfWord). Without this marker, it's just a prefix of another word. For example, if "CAR" and "CARD" are stored, the path C-A-R is shared, but the R node must have isEndOfWord = True for "CAR" to be recognized as a complete word.

Initially, this seemed inefficient. "Why not just use a HashMap where the whole word is the key? That's $O(1)$ lookup!" But then I realized: HashMaps only work for exact matches. To find all words starting with "app", you'd have to iterate through all keys—back to $O(N)$. Tries solve this prefix search problem in time proportional only to the word length ($O(L)$), which was the breakthrough I needed.

BST nodes compare values to decide left or right. Tries don't need comparison. To find character C, you just check node.children['C']. If it exists, move to it. If not, the word doesn't exist. The act of following a path is the search.

This clicked for me when I manually inserted "CAR", "CAT", "CARD", and "DO" into a Trie on paper.

Root

└─ C

└─ A

└─ R [end]

Root

└─ C

└─ A

├─ R [end]

└─ T [end]

The C and A nodes already exist, so we reuse them. We add a new child T under A. This is how memory is saved—common prefixes are shared.

Root

└─ C

└─ A

├─ R [end]

│ └─ D [end]

└─ T [end]

The path C-A-R already exists. We add D as a child of R. The R node's isEndOfWord remains True, so both "CAR" and "CARD" are valid words.

Root

├─ C

│ └─ A

│ ├─ R [end]

│ │ └─ D [end]

│ └─ T [end]

└─ D

└─ O [end]

A completely new path D-O is created from the root. No prefix is shared with the C branch.

This visualization made it clear: Tries maximize prefix sharing. "CAT" and "CAR" share "CA", so that part is stored once, and the structure branches after. This is the key to memory efficiency—though paradoxically, Tries can also waste massive amounts of memory (more on that later).

A Trie node typically consists of two main components:

children: A collection of pointers to child nodes

Node* children[26] (for lowercase English only)unordered_map<char, Node*> children (saves memory, slightly slower)isEndOfWord: A boolean flag indicating if a valid word ends at this node

Some implementations add word frequency, user click weight, or other metadata for autocomplete ranking.

Insert(word):

1. current = root

2. for each char in word:

if char not in current.children:

current.children[char] = new TrieNode()

current = current.children[char]

3. current.isEndOfWord = True

Time Complexity: $O(L)$ (where L = word length)

Space Complexity: Worst case $O(L)$ (when all characters create new nodes)

Search(word):

1. current = root

2. for each char in word:

if char not in current.children:

return False

current = current.children[char]

3. return current.isEndOfWord

Time Complexity: $O(L)$

Step 3 is crucial. Even if you successfully traverse the entire path, if isEndOfWord is False, the word doesn't exist in the Trie. For example, if only "CARD" is inserted (not "CAR"), searching for "CAR" would reach the R node but return False because R.isEndOfWord is False.

StartsWith(prefix):

1. current = root

2. for each char in prefix:

if char not in current.children:

return False

current = current.children[char]

3. return True # Successfully reached prefix end

Time Complexity: $O(L)$

Almost identical to Search, but doesn't check isEndOfWord. We only care if the prefix path exists. This can be extended to "find all words starting with this prefix" by performing DFS/BFS from the prefix node to collect all nodes where isEndOfWord == True.

Deletion is trickier. Simply setting isEndOfWord = False works if the node is part of another word's path, but if it's a dead-end branch, we should remove the node to prevent memory leaks.

Delete(word):

1. Recursively traverse to the end of the word

2. On backtrack, check each node:

- If it has no children and isn't end-of-word → delete it

- If it has children or marks another word's end → keep it

Time Complexity: $O(L)$

Implementations use recursion or explicit stacks for backtracking. Deletion isn't common in read-heavy systems (search logs are rarely deleted), but it's essential for dynamic dictionaries.

| Operation | Trie | HashMap | Binary Search Tree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exact Search | $O(L)$ | $O(L)$ (hashing) | $O(L \log N)$ (string comparison included) |

| Prefix Search | $O(L)$ | $O(N \cdot L)$ (full scan) | $O(L \log N + K)$ (K = result count) |

| Insert | $O(L)$ | $O(L)$ | $O(L \log N)$ |

| Space Complexity | $O(ALPHABET \cdot N \cdot L)$ | $O(N \cdot L)$ | $O(N \cdot L)$ |

For example, with 26 lowercase letters stored in arrays, each node needs 26 pointers (typically 8 bytes each on 64-bit systems = 208 bytes). Storing "HELLO" requires 5 nodes × 208 bytes = over 1KB, most of which are null pointers.

The first wall I hit when trying to use Tries in production was memory waste. Theoretically, sharing common prefixes should be efficient, but in practice, each node must pre-allocate space for all possible next characters.

Suppose we build an English dictionary (lowercase letters only):

Node* children[26] + bool isEndOfWord = 26 × 8 bytes + 1 byte ≈ 209 bytesFor languages like Korean, it's worse. Korean has 19 initial consonants × 21 medial vowels × 28 final consonants = 11,172 possible syllables. An array-based node would be tens of KB. HashMaps become mandatory.

# Array approach - fast but memory-hungry

class TrieNodeArray:

def __init__(self):

self.children = [None] * 26 # 26 pointer slots

self.is_end = False

# HashMap approach - slower but memory-efficient

class TrieNodeDict:

def __init__(self):

self.children = {} # Only stores what's used

self.is_end = False

Production systems almost always use HashMaps. The speed difference ($O(1)$ array access vs HashMap's average $O(1)$, worst $O(k)$ where k is key length) is negligible, but memory savings can be 10-100x.

The most famous optimization to reduce memory waste is the Radix Tree, also known as Patricia Trie (Practical Algorithm To Retrieve Information Coded In Alphanumeric).

In a standard Trie, storing "ROMANTIC" requires:

R -> O -> M -> A -> N -> T -> I -> C [end]

8 nodes. At 209 bytes each, that's about 1.6KB.

In a Radix Tree:

ROMANTIC [end]

A single node stores the entire string. If "ROME" is later added:

ROM

├─ ANTIC [end]

└─ E [end]

The common portion "ROM" is stored in one node, then branches. This drastically reduces node count.

/api/users/profile/settings/privacy rarely branch in the middleReal-World Examples:

Theory is understood—now let's build a working autocomplete.

class TrieNode:

def __init__(self):

self.children = {} # HashMap for memory efficiency

self.is_end_of_word = False

self.word = None # Store complete word for autocomplete

class Trie:

def __init__(self):

self.root = TrieNode()

def insert(self, word):

"""Insert word - O(L)"""

node = self.root

for char in word:

if char not in node.children:

node.children[char] = TrieNode()

node = node.children[char]

node.is_end_of_word = True

node.word = word # Easy to retrieve later

def search(self, word):

"""Exact word search - O(L)"""

node = self.root

for char in word:

if char not in node.children:

return False

node = node.children[char]

return node.is_end_of_word

def starts_with(self, prefix):

"""Check if prefix exists - O(L)"""

node = self.root

for char in prefix:

if char not in node.children:

return False

node = node.children[char]

return True

def autocomplete(self, prefix, limit=10):

"""

Return up to 'limit' words starting with prefix

Time Complexity: O(L + K × M)

- L: prefix length (navigating to prefix node)

- K: number of results

- M: average word length (DFS traversal)

"""

node = self.root

# Step 1: Navigate to prefix end

for char in prefix:

if char not in node.children:

return [] # Prefix doesn't exist

node = node.children[char]

# Step 2: DFS to collect all words from this node

results = []

self._dfs_collect(node, results, limit)

return results

def _dfs_collect(self, node, results, limit):

"""DFS to find all end-of-word nodes"""

if len(results) >= limit:

return # Early termination

if node.is_end_of_word:

results.append(node.word)

# Traverse children in sorted order (alphabetical results)

for char in sorted(node.children.keys()):

self._dfs_collect(node.children[char], results, limit)

def delete(self, word):

"""

Delete word - O(L)

Clean up empty nodes during backtracking

"""

def _delete_recursive(node, word, index):

if index == len(word):

# Reached end - remove word marker

if not node.is_end_of_word:

return False # Word didn't exist

node.is_end_of_word = False

node.word = None

# Can delete node if no children

return len(node.children) == 0

char = word[index]

if char not in node.children:

return False # Path doesn't exist

child = node.children[char]

should_delete_child = _delete_recursive(child, word, index + 1)

if should_delete_child:

# Delete child node

del node.children[char]

# Check if current node can be deleted

return len(node.children) == 0 and not node.is_end_of_word

return False

_delete_recursive(self.root, word, 0)

# Build dictionary

trie = Trie()

words = ["apple", "app", "application", "apply", "apricot",

"banana", "band", "bandana", "can", "cat", "car"]

for word in words:

trie.insert(word)

# Autocomplete tests

print(trie.autocomplete("app"))

# Output: ['app', 'apple', 'application', 'apply']

print(trie.autocomplete("ban"))

# Output: ['banana', 'band', 'bandana']

print(trie.autocomplete("ca"))

# Output: ['can', 'car', 'cat']

# Exact search

print(trie.search("app")) # True

print(trie.search("appl")) # False (no end marker)

print(trie.search("application")) # True

# Delete and re-search

trie.delete("app")

print(trie.search("app")) # False

print(trie.autocomplete("app")) # ['apple', 'application', 'apply']

# "app" is gone, but the path remains for other words

Routers determine the next hop by matching the network portion of IP addresses. For example:

192.168.1.0/24 → Gateway A192.168.0.0/16 → Gateway B0.0.0.0/0 (default) → Gateway CFor IP 192.168.1.50, the router finds the longest matching prefix (/24). This Longest Prefix Match is efficiently implemented with Tries (especially Radix Trees).

Binary Trie for IP routing:

Root

└─ 1 (first bit of 192 = 11000000)

└─ 1

└─ 0

... (32-bit depth)

In practice, routers use octet-level (8-bit) compressed Radix Trees.

Old feature phones used T9 (Text on 9 keys):

Typing 4663 could mean "GOOD", "HOME", "GONE", etc. The Trie stores words converted to digit sequences, ranked by frequency.

To correct typos, we need to find words "similar" to the input. Traverse the Trie while computing edit distance (Levenshtein Distance), collecting words within distance 1-2.

def fuzzy_search(trie_node, word, max_distance):

"""

Find words within max_distance edit distance

Uses Dynamic Programming + Trie traversal

"""

# DP array tracks edit distance while traversing

# Complex implementation - libraries like SymSpell or BK-tree recommended

A hybrid of Tries and BSTs. Each node has 3 children:

Uses less memory than Tries but search is $O(L \log \Sigma)$ instead of $O(L)$. Rarely used in practice but considered for embedded systems.

Used in Japanese morphological analyzers like MeCab and Kuromoji. Represents a Trie using two arrays (BASE and CHECK) for extreme memory efficiency. Implementation is very complex, but achieves best-in-class performance for read-only large dictionaries.

Before deploying Tries to production:

| Technology | Advantages | Disadvantages | Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trie (In-memory) | Fast prefix search | High memory | Small autocomplete |

| Elasticsearch | Distributed, full-text | Operational complexity | Large search engines |

| Redis Sorted Set | Simple, scoring | Inefficient prefix search | Ranking-based suggestions |

| PostgreSQL LIKE | No extra setup | Slow (without index) | Small DB queries |

| SQLite FTS5 | Lightweight, embedded | Limited advanced features | Mobile app search |

What I ultimately accepted: Tries are specialized tools optimized for the specific problem of prefix search. They're not a silver bullet. But for autocomplete, dictionary lookup, and IP routing—anywhere you need to "quickly find things matching the beginning"—they deliver irreplaceable performance.

Memory issues can be mitigated with HashMap-based nodes, Radix Trees, or external storage. The key is accurately understanding the problem characteristics and making an informed choice based on Tries' strengths and weaknesses.

Every time I type in Google's search box and suggestions appear instantly, I now know there's a Trie behind the scenes scanning millions of words in $O(L)$ time. When that clicked, Tries became more than just a data structure—they became a core technology enabling real-time user experiences.